|

CGAL 5.0.3 - 2D Arrangements

|

|

CGAL 5.0.3 - 2D Arrangements

|

Given a set \( \cal C\) of planar curves, the arrangement \( \cal A(\cal C)\) is the subdivision of the plane into zero-dimensional, one-dimensional and two-dimensional cells, called vertices, edges and faces, respectively induced by the curves in \( \cal C\). Arrangements are ubiquitous in the computational-geometry literature and have many applications; see, e.g., [1], [5].

The curves in \( \cal C\) can intersect each other (a single curve may also be self-intersecting or may be comprised of several disconnected branches) and are not necessarily \( x\)-monotone.A continuous planar curve \( C\) is \( x\)-monotone if every vertical line intersects it at most once. For example, a non-vertical line segment is always \( x\)-monotone and so is the graph of any continuous function \( y = f(x)\). For convenience, we treat vertical line segments as weakly \( x\)-monotone, as there exists a single vertical line that overlaps them. A circle of radius \( r\) centered at \( (x_0, y_0)\) is not \( x\)-monotone, as the vertical line \( x = x_0\) intersects it at \( (x_0, y_0 - r)\) and at \( (x_0, y_0 + r)\). We construct a collection \( \cal C''\) of \( x\)-monotone subcurves that are pairwise disjoint in their interiors in two steps as follows. First, we decompose each curve in \( \cal C\) into maximal \( x\)-monotone subcurves (and possibly isolated points), obtaining the collection \( \cal C'\). Note that an \( x\)-monotone curve cannot be self-intersecting. Then, we decompose each curve in \( \cal C'\) into maximal connected subcurves not intersecting any other curve (or point) in \( \cal C'\). The collection \( \cal C''\) may also contain isolated points, if the curves of \( \cal C\) contain such points. The arrangement induced by the collection \( \cal C''\) can be conveniently embedded as a planar graph, whose vertices are associated with curve endpoints or with isolated points, and whose edges are associated with subcurves. It is easy to see that \( \cal A(\cal C) = \cal A(\cal C'')\). This graph can be represented using a doubly-connected edge list data-structure (Dcel for short), which consists of containers of vertices, edges and faces and maintains the incidence relations among these objects.

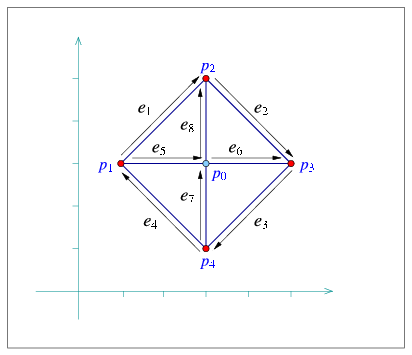

The main idea behind the Dcel data-structure is to represent each edge using a pair of directed halfedges, one going from the \( xy\)-lexicographically smaller (left) endpoint of the curve toward its the \( xy\)-lexicographically larger (right) endpoint, and the other, known as its twin halfedge, going in the opposite direction. As each halfedge is directed, we say it has a source vertex and a target vertex. Halfedges are used to separate faces, and to connect vertices (with the exception of isolated vertices, which are unconnected).

If a vertex \( v\) is the target of a halfedge \( e\), we say that \( v\) and \( e\) are incident to each other. The halfedges incident to a vertex \( v\) form a circular list oriented in a clockwise order around this vertex. (An isolated vertex has no incident halfedges.)

Each halfedge \( e\) stores a pointer to its incident face, which is the face lying to its left. Moreover, every halfedge is followed by another halfedge sharing the same incident face, such that the target vertex of the halfedge is the same as the source vertex of the next halfedge. The halfedges are therefore connected in circular lists, and form chains, such that all edges of a chain are incident to the same face and wind along its boundary. We call such a chain a connected component of the boundary (or CCB for short).

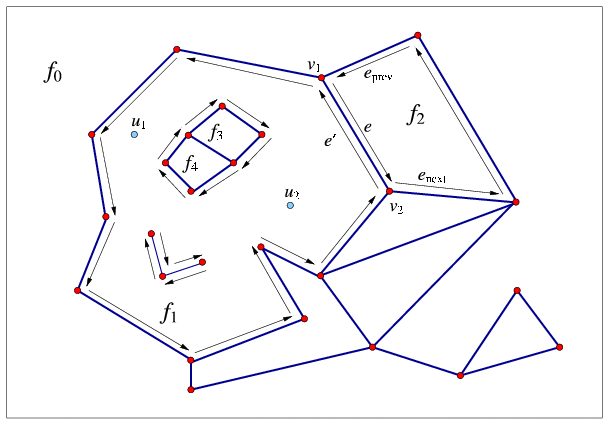

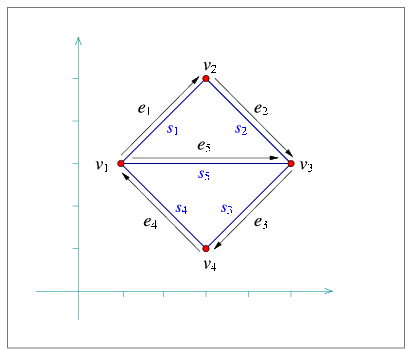

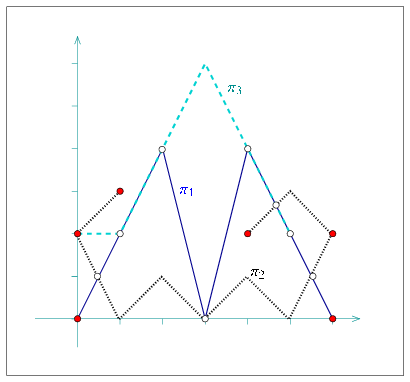

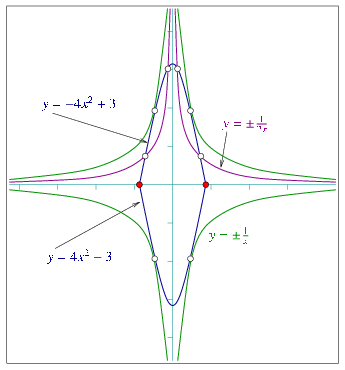

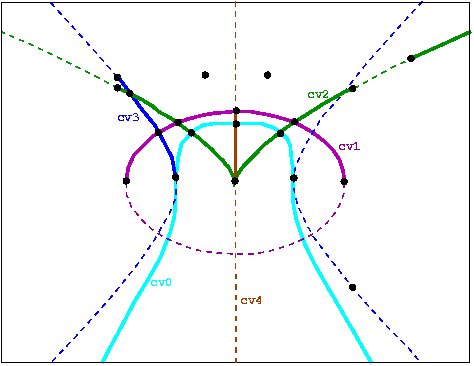

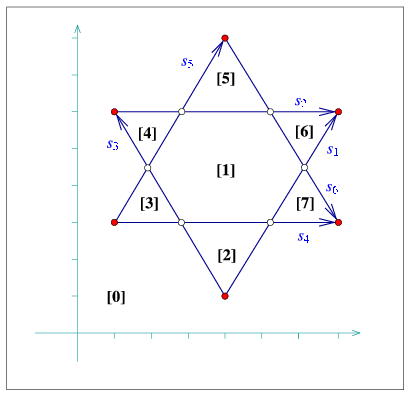

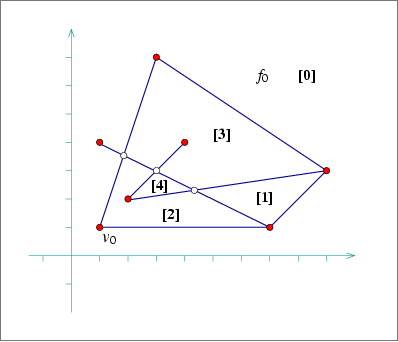

The unique CCB of halfedges winding in a counterclockwise orientation along a face boundary is referred to as the outer CCB of the face. For the time being let us consider only arrangements of bounded curves, such that exactly one unbounded face exists in every arrangement. The unbounded face does not have an outer boundary. Any other connected component of the boundary of the face is called a hole (or inner CCB), and can be represented as a circular chain of halfedges winding in a clockwise orientation around it. Note that a hole does not necessarily correspond to a single face, as it may have no area, or alternatively it may consist of several connected faces. Every face can have several holes contained in its interior (or no holes at all). In addition, every face may contain isolated vertices in its interior. See Figure 34.1 for an illustration of the various Dcel features. For more details on the Dcel data structure see [3] Chapter 2.

The \( x\)-monotone curves of an arrangement are embedded in an rectangular two-dimensional area called the parameter space.The term parameter space stems from a major extension the arrangement package is going through to support arrangements embedded on certain two-dimensional parametric surfaces in three-dimensions (or higher). The parameter space is defined as \( X \times Y\), where \( X\) and \( Y\) are open, half-open, or closed intervals with endpoints in the compactified real line \( \mathbb{R} \cup \{-\infty,+\infty\}\). Let \( b_l\), \( b_r\), \( b_b\), and \( b_t\) denote the endpoints of \( X\) and \( Y\), respectively. We typically refer to these values as the left, right, bottom, and top sides of the boundary of the parameter space. If the parameter space is, for example, the entire compactified plane, which is currently the only option supported by the package, \( b_l = b_b = -\infty\) and \( b_r = b_t = +\infty\).

The rest of this chapter is organized as follows: In Section The Main Arrangement Class we review in detail the interface of the Arrangement_2 class-template, which is the central component in the arrangement package. In Section Issuing Queries on an Arrangement we show how queries on an arrangement can be issued. In Section Free Functions in the Arrangement Package we review some important free (global) functions that operate on arrangements, the most important ones being the free insertion-functions. Section Traits Classes contains detailed descriptions of the various geometric traits classes included in the arrangement package. Using these traits classes it is possible to construct arrangements of different families of curves. In Section The Notification Mechanism we review the notification mechanism that allows external classes to keep track of the changes that an arrangement instance goes through. Section Extending the DCEL explains how to extend the Dcel records, to store extra data with them, and to efficiently update this data. In Section Overlaying Arrangements we introduce the fundamental operation of overlaying two arrangements. Section Storing the Curve History describes the Arrangement_with_history_2 class-template that extends the arrangement by storing additional history records with its curves. Finally, in Section Input/Output Streams we review the arrangement input/output functions.

The class Arrangement_2<Traits,Dcel> is the main class in the arrangement package. It is used to represent planar arrangements and it provides the interface needed to construct them, traverse them, and maintain them. An arrangement is defined by a geometric traits class that determines the family of planar curves that form the arrangement, and a Dcel class, which represents the topological structure of the planar subdivision. It supplies a minimal set of geometric operations (predicates and constructions) required to construct and maintain the arrangement and to operate on it.

The design of the arrangement package is guided by the need to separate between the representation of the arrangements and the various geometric algorithms that operate on them, and by the need to separate between the topological and geometric aspects of the planar subdivision. The separation is exhibited by the two template parameters of the Arrangement_2 template:

The Traits template-parameter should be instantiated with a model of the ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept and optionally additional geometry traits concepts. A model of the ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept defines the types of \( x\)-monotone curves and two-dimensional points, namely X_monotone_curve_2 and Point_2, respectively, and supports basic geometric predicates on them.

In the first sections of this chapter we always use Arr_segment_traits_2 as our traits class, to construct arrangements of line segments. However, the arrangement package contains several other traits classes that can handle other types of curves, such as polylines (continuous piecewise-linear curves), conic arcs, and arcs of rational functions. We exemplify the usage of these traits classes in Section Traits Classes.

Dcel template-parameter should be instantiated with a class that is a model of the ArrangementDcel concept. The value of this parameter is Arr_default_dcel<Traits> by default. However, in many applications it is necessary to extend the Dcel features; see Section Extending the DCEL for further explanations and examples.

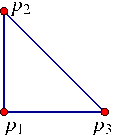

The simple program listed below constructs a planar map of three line segments forming a triangle. The constructed arrangement is instantiated with the Arr_segment_traits_2 traits class to handle segments only. The resulting arrangement consists of two faces, a bounded triangular face and the unbounded face. The program is not very useful as it is, since it ends immediately after the arrangement is constructed. We give more enhanced examples in the rest of this chapter.

The simplest and most fundamental arrangement operations are the various traversal methods, which allow users to systematically go over the relevant features of the arrangement at hand.

As mentioned above, the arrangement is represented as a Dcel, which stores three containers of vertices, halfedges and faces. Thus, the Arrangement_2 class supplies iterators for these containers. For example, the methods vertices_begin() and vertices_end() return Arrangement_2::Vertex_iterator objects that define the valid range of arrangement vertices. The value type of this iterator is Arrangement_2::Vertex. Moreover, the vertex-iterator type is equivalent to Arrangement_2::Vertex_handle, which serves as a pointer to a vertex. As we show next, all functions related to arrangement features accept handle types as input parameters and return handle types as their output.

In addition to the iterators for arrangement vertices, halfedges and faces, the arrangement class also provides edges_begin() and edges_end() that return Arrangement_2::Edge_iterator objects for traversing the arrangement edges. Note that the value type of this iterator is Arrangement_2::Halfedge, representing one of the twin halfedges that represent the edge.

All iterator, circulatorA circulator is used to traverse a circular list, such as the list of halfedges incident to a vertex - see below. and handle types also have non-mutable (const) counterparts. These non-mutable iterators are useful to traverse an arrangement without changing it. For example, the arrangement has a non-constant member function called vertices_begin() that returns a Vertex_iterator object and another const member function that returns a Vertex_const_iterator object. In fact, all methods listed in this section that return an iterator, a circulator or a handle have non-mutable counterparts. It should be noted that, for example, Vertex_handle can be readily converted into a Vertex_const_handle, but not vice-verse.

Conversion of a non-mutable handle to a corresponding mutable handle are nevertheless possible, and can be performed using the static function Arrangement_2::non_const_handle() (see, e.g., Section Point-Location Queries). There are three variant of this function, one for each type of handle.

A vertex is always associated with a geometric entity, namely with a Point_2 object, which can be obtained by the point() method of the Vertex class nested within Arrangement_2.

The is_isolated() method determines whether a vertex is isolated or not. Recall that the halfedges incident to a non-isolated vertex, namely the halfedges that share a common target vertex, form a circular list around this vertex. The incident_halfedges() method returns a circulator of type Arrangement_2::Halfedge_around_vertex_circulator that enables the traversal of this circular list in a clockwise direction. The value type of this circulator is Halfedge.

The following function prints all the neighbors of a given arrangement vertex (assuming that the Point_2 type can be inserted into the standard output using the << operator). The arrangement type is the same as in the simple example above.

In case of an isolated vertex, it is possible to obtain the face that contains this vertex using the face() method.

Each arrangement edge, realized as a pair of twin halfedges, is associated with an X_monotone_curve_2 object, which can be obtained by the curve() method of the Halfedge class nested in the Arrangement_2 class.

The source() and target() methods return handles to the halfedge source and target vertices respectively. We can obtain a handle to the twin halfedge using the twin() method. From the definition of halfedges, it follows that if he is a halfedge handle, then:

he->curve() is equivalent to he->twin()->curve(), he->source() is equivalent to he->twin()->target(), and he->target() is equivalent to he->twin()->source(). Every halfedge has an incident face that lies to its left, which can be obtained by the face() method. Recall that a halfedge is always one link in a connected chain of halfedges that share the same incident face, known as a CCB. The prev() and next() methods return handles to the previous and next halfedges in the CCB respectively.

As the CCB is a circular list of halfedges, it is only natural to traverse it using a circulator. The ccb() method returns a Arrangement_2::Ccb_halfedge_circulator object for the halfedges along the CCB.

The function print_ccb() listed below prints all \( x\)-monotone curves along a given CCB (assuming that the Point_2 and the X_monotone_curve_2 types can be inserted into the standard output using the << operator).

An arrangement of bounded curves always has a single unbounded face. The function unbounded_face() returns a handle to this face. (Note that an empty arrangement contains nothing but the unbounded face.)

Given a Face object, we can use the is_unbounded() method to determine whether it is unbounded. Bounded faces have an outer CCB, and the outer_ccb() method returns a circulator for the halfedges along this CCB. Note that the halfedges along this CCB wind in a counterclockwise orientation around the outer boundary of the face.

A face can also contain disconnected components in its interior, namely holes and isolated vertices:

holes_begin() and holes_end() methods return Arrangement_2::Hole_iterator iterators that define the range of holes inside the face. The value type of this iterator is Ccb_halfedge_circulator, defining the CCB that winds in a clockwise orientation around a hole. isolated_vertices_begin() and isolated_vertices_end() methods return Arrangement_2::Isolated_vertex_iterator iterators that define the range of isolated vertices inside the face. The value type of this iterator is Vertex. The function print_face() listed below prints the outer and inner boundaries of a given face, using the function print_ccb(), which was introduced in the previous subsection.

The function listed below prints the current setting of a given arrangement. This concludes the preview of the various traversal methods.The file arr_print.h, which can be found under the examples folder, includes this function and the rest of the functions listed in this section. Over there they are written in a more generic fashion, where the arrangement type serves as a template parameter for these functions, so different instantiations of the Arrangement_2<Traits,Dcel> template can be provided to the same function templates.

In this section we review the various member functions of the Arrangement_2 class that allow users to modify the topological structure of the arrangement by introducing new edges or vertices, modifying them, or removing them.

The arrangement member-functions that insert new curves into the arrangement, thus enabling the construction of a planar subdivision, are rather specialized, as they require a-priori knowledge on the location of the inserted curve. Indeed, for most purposes it is more convenient to construct an arrangement using the free (global) insertion-functions.

The most important functions that allow users to modify the arrangement, and perhaps the most frequently used ones, are the specialized insertion functions of \( x\)-monotone curves whose interior is disjoint from any other curve in the existing arrangement and do not contain any vertex of the arrangement. In addition, these function require that the location of the curve in the arrangement is known.

The motivation behind these rather harsh restrictions on the nature of the inserted curves is the decoupling of the topological arrangement representation from the various algorithms that operate on it. While the insertion of an \( x\)-monotone curve whose interior is disjoint from all existing arrangement features is quite straightforward (as we show next), inserting curves that intersect with the curves already inserted into the arrangement is much more complicated and requires the application of non-trivial geometric algorithms. These insertion operations are therefore implemented as free functions that operate on the arrangement and the inserted curve(s); see Section Free Functions in the Arrangement Package for more details and examples. You may skip to Section Free Functions in the Arrangement Package, and return to this subsection at a later point in time.

When an \( x\)-monotone curve is inserted into an existing arrangement, such that the interior of this curve is disjoint from any arrangement feature, only the following three scenarios are possible, depending on the status of the endpoints of the inserted subcurve:

The Arrangement_2 class offers insertion functions named insert_in_face_interior(), insert_from_left_vertex(), insert_from_right_vertex() and insert_at_vertices() that perform the special insertion procedures listed above. The first function accepts an \( x\)-monotone curve \( c\) and an arrangement face \( f\) that contains this curve in its interior. The other functions accept an \( x\)-monotone curve \( c\) and handles to the existing vertices that correspond to the curve endpoint(s). Each of the four functions returns a handle to one of the twin halfedges that have been created, where:

insert_in_face_interior(c, f) returns a halfedge directed from the vertex corresponding to the left endpoint of c toward the vertex corresponding to its right endpoint. insert_from_left_vertex(c, v) and insert_from_right_vertex(c, v) returns a halfedge whose source is the vertex \( v\) that and whose target is the new vertex that has just been created. insert_at_vertices(c, v1, v2) returns a halfedge directed from \( v_1\) to \( v_2\).

edge_insertion.cpp. The arrows mark the direction of the halfedges returned from the various insertion functions. The following program demonstrates the usage of the four insertion functions. It creates an arrangement of five line segments, as depicted in Figure 34.3 Notice that in all figures in the rest of this chapter the coordinate axes are drawn only for illustrative purposes and are not part of the arrangement.. As the arrangement is very simple, we use the simple Cartesian kernel of CGAL with integer coordinates for the segment endpoints. We also use the Arr_segment_traits_2 class that enables the efficient maintenance of arrangements of line segments; see more details on this traits class in Section Traits Classes. This example, as many others in this chapter, uses some print-utility functions from the file print_arr.h; these functions are also listed in Section Traversing the Arrangement.

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/edge_insertion.cpp

Observe that the first line segment is inserted in the interior of the unbounded face. The other line segments are inserted using the vertices created by the insertion of previous segments. The resulting arrangement consists of three faces, where the two bounded faces form together a hole in the unbounded face.

Isolated points are in general simpler geometric entities than curves and indeed the member functions that manipulate them are easier to understand.

The function insert_in_face_interior(p, f) inserts an isolated point \( p\), located in the interior of a given face \( f\), into the arrangement and returns a handle to the arrangement vertex it has created and associated with \( p\). Naturally, this function has a precondition that \( p\) is really an isolated point, namely it does not coincide with any existing arrangement vertex and does not lie on any edge. As mentioned in Section Traversing the Arrangement, it is possible to obtain the face containing an isolated vertex handle \( v\) by calling v->face().

The function remove_isolated_vertex(v) receives a handle to an isolated vertex and removes it from the arrangement.

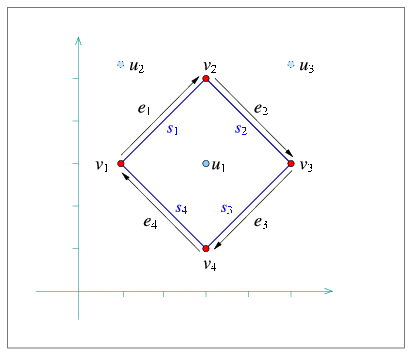

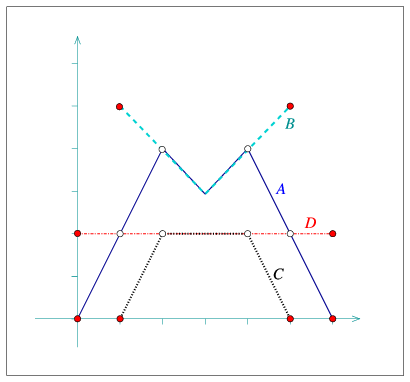

isolated_vertices.cpp. The vertices \( u_2\) and \( u_3\) are eventually removed from the arrangement. The following program demonstrates the usage of the arrangement member-functions for manipulating isolated vertices. It first inserts three isolated vertices located inside the unbounded face, then it inserts four line segments that form a rectangular hole inside the unbounded face (see Figure 34.3 for an illustration). Finally, it traverses the vertices and removes those isolated vertices that are still contained in the unbounded face ( \( u_2\) and \( u_3\) in this case):

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/isolated_vertices.cpp

In the previous subsection we showed how to introduce new isolated vertices in the arrangement. But how does one create a vertex that lies on an existing arrangement edge (more precisely, on an \( x\)-monotone curve that is associated with an arrangement edge)?

It should be noted that such an operation involves the splitting of a curve at a given point in its interior, while the traits class used by Arrangement_2 does not necessarily have the ability to perform such a split operation. However, if users have the ability to split an \( x\)-monotone curve into two at a given point \( p\) (this is usually the case when employing a more sophisticated traits class; see Section Traits Classes for more details) they can use the split_edge(e, c1, c2) function, were \( c_1\) and \( c_2\) are the two subcurves resulting from splitting the \( x\)-monotone curve associated with the halfedge \( e\) at some point (call it \( p\)) in its interior. The function splits the halfedge pair into two pairs, both incident to a new vertex \( v\) associated with \( p\), and returns a handle to a halfedge whose source equals \( e\)'s source vertex and whose target is the new vertex \( v\).

The reverse operation is also possible. Suppose that we have a vertex \( v\) of degree \( 2\), whose two incident halfedges, \( e_1\) and \( e_2\), are associated with the curves \( c_1\) and \( c_2\). Suppose further that it is possible to merge these two curves into a single continuous \( x\)-monotone curve \( c\). Calling merge_edge(e1, e2, c) will merge the two edges into a single edge associated with the curve \( c\), essentially removing the vertex \( v\) from the arrangement.

Finally, the function remove_edge(e) removes the edge \( e\) from the arrangement. Note that this operation is the reverse of an insertion operation, so it may cause a connected component to split into two, or two faces to merge into one, or a hole to disappear. By default, if the removal of e causes one of its end-vertices to become isolated, we remove this vertex as well. However, users can control this behavior and choose to keep the isolated vertices by supplying additional Boolean flags to remove_edge() indicating whether the source and the target vertices are to be removed should they become isolated.

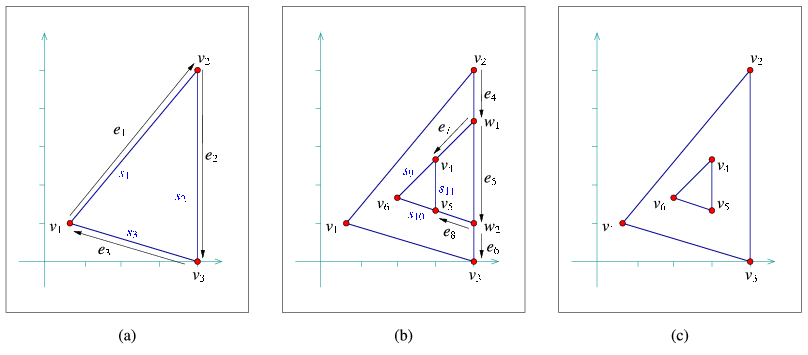

edge_manipulation.cpp. Note that the edges \( e_7\) and \( e_8\) and the vertices \( w_1\) and \( w_2\), introduced in step (b) are eventually removed in step (c). In the following example program we show how the edge-manipulation functions can be used. The program works in three steps, as demonstrated in Figure 34.4. Note that here we still stick to integer coordinates, but as we work on a larger scale we use an unbounded integer number-type (in this case, the Gmpz type taken from the Gmp library) instead of the built-in int type.As a rule of thumb, one can use a bounded integer type for representing line segments whose coordinates are bounded by \( \lfloor\sqrt[3]{M}\rfloor\), where \( M\) is the maximal representable integer value. This guarantees that no overflows occur in the computations carried out by the traits class, hence all traits-class predicates always return correct results. In case the Gmp library is not installed (as indicated by the CGAL_USE_GMP flag defined in CGAL/basic.h), we use MP_Float, a number-type included in CGAL's support library that is capable of storing floating-point numbers with unbounded mantissa. We also use the standard Cartesian kernel of CGAL as our kernel. This is recommended when the kernel is instantiated with a more complex number type, as we demonstrate in other examples in this chapter.

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/edge_manipulation.cpp

Note how we use the halfedge handles returned from split_edge() and merge_edge(). Also note the insertion of the isolated vertex \( v_6\) located inside the triangular face (the incident face of \( e_7\)). This vertex seizes from being isolated, as it is gets connected to other vertices.

In this context, we should mention the two member functions modify_vertex(v, p), which sets \( p\) to be the point associated with the vertex \( v\), and modify_edge(e, c), which sets \( c\) to be the \( x\)-monotone curve associated with the halfedge \( e\). These functions have preconditions that \( p\) is geometrically equivalent to v->point() and \( c\) is equivalent to e->curve() (i.e., the two curves have the same graph), respectively, to avoid the invalidation of the geometric structure of the arrangement. At a first glance it may seen as these two functions are of little use. However, we should keep in mind that there may be extraneous data (probably non-geometric) associated with the point objects or with the curve objects, as defined by the traits class. With these two functions we can modify this data; see more details in Section Traits Classes.

In addition, we can use these functions to replace a geometric object (a point or a curve) with an equivalent object that has a more compact representation. For example, we can replace the point \( (\frac{20}{40}, \frac{99}{33})\) associated with some vertex \( v\), by \( (\frac{1}{2}, 3)\).

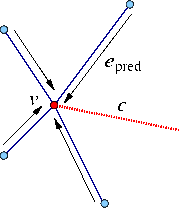

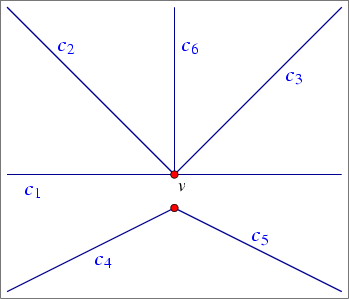

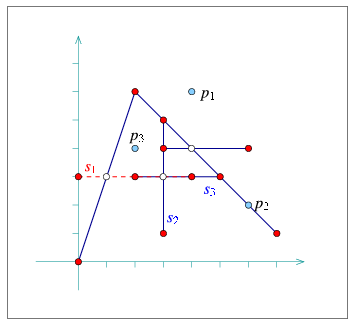

Assume that the specialized insertion function insert_from_left_vertex(c,v) is invoked for a curve \( c\), whose left endpoint is already associated with a non-isolated vertex \( v\). Namely, \( v\) has already several incident halfedges. It is necessary in this case to locate the exact place for the new halfedge mapped to the inserted new curve \( c\) in the circular list of halfedges incident to \( v\). More precisely, it is sufficient to locate one of the halfedges pred directed toward \( v\) such that \( c\) is located between pred and pred->next() in clockwise order around \( v\), in order to complete the insertion (see Figure 34.2 for an illustration). This may take \( O(d)\) time where \( d\) is the degree of the vertex. However, if the halfedge pred is known in advance, the insertion can be carried out in constant time.

The Arrangement_2 class provides the advanced versions of the specialized insertion functions for a curve \( c\) - namely we have insert_from_left_vertex(c,pred) and insert_from_right_vertex(c,pred) that accept a halfedge pred as specified above, instead of a vertex \( v\). These functions are more efficient, as they take constant time and do not perform any geometric operations. Thus, they should be used when the halfedge pred is known. In case that the vertex \( v\) is isolated or that the predecessor halfedge for the new inserted curve is not known, the simpler versions of these insertion functions should be used.

Similarly, there exist two overrides of the insert_at_vertices() function: One that accept the two predecessor halfedges around the two vertices \( v_1\) and \( v_2\) that correspond to the curve endpoints, and one that accepts a handle for one vertex and a predecessor halfedge around the other vertex.

special_edge_insertion.cpp. Note that \( p_0\) is initially inserted as an isolated point and later on connected to the other four vertices. The following program shows how to construct the arrangement depicted in Figure 34.5 using the specialized insertion functions that accept predecessor halfedges:

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/special_edge_insertion.cpp

It is possible to perform even more refined operations on an Arrangement_2 instance given specific topological information. As most of these operations are very fragile and perform no precondition testing on their input in order to gain efficiency, they are not included in the public interface of the arrangement class. Instead, the Arr_accessor<Arrangement> class allows access to these internal arrangement operations - see more details in the Reference Manual.

One of the most important query types defined on arrangements is the point-location query: Given a point, find the arrangement cell that contains it. Typically, the result of a point-location query is one of the arrangement faces, but in degenerate situations the query point can be located on an edge or it may coincide with a vertex.

Point-location queries are common in many applications, and also play an important role in the incremental construction of arrangements (and more specifically in the free insertion-functions described in Section Free Functions in the Arrangement Package). Therefore, it is crucial to have the ability to answer such queries effectively.

The Arrangement_2 class template does not support point-location queries directly, as the arrangement representation is decoupled from the geometric algorithms that operate on it. The 2D Arrangements package includes a set of class templates that are capable of answering such queries; all are models of the concept ArrangementPointLocation_2. Each model employs a different algorithm or strategy for answering queries. A model of this concept must define the locate() member function, which accepts an input query-point and returns an object that represents the arrangement cell that contains this point. This object is is type Arr_point_location_result<Arrangement_2>::Type—a discriminated union container of the bounded types Vertex_const_handle, Halfedge_const_handle, or Face_const_handle. Depending on whether the query point is located inside a face, on an edge, or on a vertex, the appropriate handle can be obtained with value retrieval by boost::get as demonstrated in the example below.

Note that the handles returned by the locate() functions are non-mutable (const). If necessary, such handles may be cast to mutable handles using the non_const_handle() methods Arrangement_2::non_const_handle() provided by the Arrangement_2 class.

An object pl of any point-location class must be attached to an Arrangement_2 object arr before it is used to answer point-location queries on arr. This attachment can be performed when pl is constructed or at a later time using the pl.init(arr) call.

The function template listed below accepts a point-location object, the type of which is a model of the ArrangementPointLocation_2 concept, and a query point. The function template issues a point-location query for the given point, and prints out the result. It is defined in the header file point_location_utils.h.

The function template locate_point() calls an instance of the function template print_point_location(), which inserts the result of the query into the standard output-stream. It is listed below, and defined in the header file point_location_utils.h. Observe how the function boost::get() is used to cast the resulting object into a handle to an arrangement feature. The point-location object pl is assumed to be already attached to an arrangement.

Each of the various point-location class templates employs a different algorithm or strategyThe term strategy is borrowed from the design-pattern taxonomy [4], Chapter 5. A strategy provides the means to define a family of algorithms, each implemented by a separate class. All classes that implement the various algorithms are made interchangeable, letting the algorithm in use vary according to the user choice. for answering queries:

Arr_naive_point_location<Arrangement> employs the naive strategy. It locates the query point naively, exhaustively scanning all arrangement cells.

Arr_walk_along_line_point_location<Arrangement> employs the walk-along-a-line (or walk for short) strategy. It simulates a traversal, in reverse order, along an imaginary vertical ray emanating from the query point. It starts from the unbounded face of the arrangement and moves downward toward the query point until it locates the arrangement cell containing it.

Arr_landmarks_point_location<Arrangement,Generator> uses a set of landmark points, the location of which in the arrangement is known. It employs the landmark strategy. Given a query point, it uses a nearest-neighbor search-structure (a Kd-tree is used by default) to find the nearest landmark, and then traverses the straight-line segment connecting this landmark to the query point.

There are various ways to select the landmark set in the arrangement. The selection is governed by the Generator template parameter. The default generator class, namely Arr_landmarks_vertices_generator, selects all the vertices of the attached arrangement as landmarks. Additional generators that select the set in other ways, such as by sampling random points or choosing points on a grid, are also available; see the Reference Manual for more details.

The landmark strategy requires that the type of the attached arrangement be an instance of the Arrangement_2<Traits,Dcel> class template, where the Traits parameter is substituted with a geometry-traits class that models the ArrangementLandmarkTraits_2 concept, which refines the basic ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept; see Section The Landmarks Concept for details. Most traits classes included in the 2D Arrangement package are models of this refined concept.

Arr_trapezoid_ric_point_location<Arrangement> implements an improved variant of Mulmuley's point-location algorithm [8]; see also [3], Chapter 6. The (expected) query-time is logarithmic. The arrangement faces are decomposed into simpler cells each of constant complexity, known as pseudo-trapezoids, and a search structure (a directed acyclic graph) is constructed on top of these cells, facilitating the search of the pseudo trapezoid (hence the arrangement cell) containing a query point in expected logarithmic time. The trapezoidal map and the search structure are built by a randomized incremental construction algorithm (RIC).

The first two strategies do not require any extra data. The class templates that implement them store a pointer to an arrangement object and operate directly on it. Attaching such point-location objects to an existing arrangement has virtually no running-time cost at all, but the query time is linear in the size of the arrangement (the performance of the walk strategy is much better in practice, but its worst-case performance is linear). Using these strategies is therefore recommended only when a relatively small number of point-location queries are issued by the application, or when the arrangement is constantly changing (That is, changes in the arrangement structure are more frequent than point-location queries).

On the other hand, the landmarks and the trapezoid RIC strategies require auxiliary data structures on top of the arrangement, which they need to construct once they are attached to an arrangement object and need to keep up-to-date as this arrangement changes. The data structure needed by the landmarks strategy can be constructed in \( O(N \log N) \) time, where \( N \) is the overall number of edges in the arrangement, but the constant hidden in the \( O() \) notation for the trapezoidal map RIC strategy is much larger. Thus, construction needed by the landmark algorithm is in practice significantly faster than the construction needed by the trapezoidal map RIC strategy. In addition, although both resulting data structures are asymptotically linear in size, using a Kd-tree as the nearest-neighbor search-structure that the landmark algorithm stores significantly reduces memory consumption. The trapezoidal map RIC algorithm has expected logarithmic query time, while the query time for the landmark strategy may be as large as linear. In practice however, the query times of both strategies are competitive. For a detailed experimental comparison see [6].

Updating the auxiliary data structures of the trapezoidal map RIC algorithm is done very efficiently. On the other hand, updating the nearest-neighbor search-structure of the landmark algorithm may consume more time when the arrangement changes frequently, especially when a Kd-tree is used, as it must be rebuilt each time the arrangement changes. It is therefore recommended that the Arr_landmarks_point_location class template be used when the application frequently issues point-location queries on an arrangement that only seldom changes. If the arrangement is more dynamic and is frequently going through changes, the Arr_trapezoid_ric_point_location class template should be the selected point-location strategy.

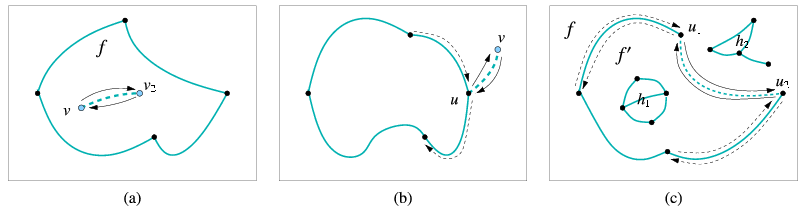

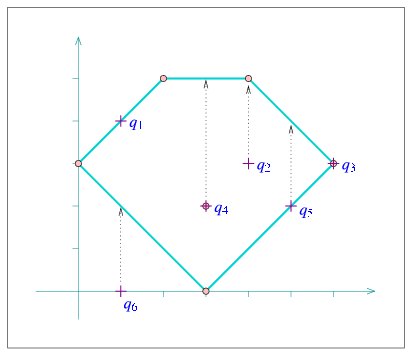

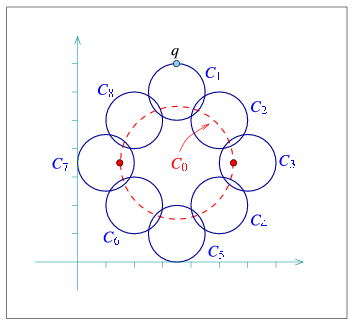

point_location_example.cpp, vertical_ray_shooting.cpp, and batched_point_location.cpp. The arrangement vertices are drawn as small discs, while the query points \( q_1, \ldots, q_6\) are marked with crosses. The program listed below constructs a simple arrangement of five line segments that form a pentagonal face, with a single isolated vertex in its interior, as depicted in Figure 34.6. Notice that we use the same arrangement structure in the next three example programs. The arrangement construction is performed by the function construct_segment_arr() defined in the header file point_location_utils.h. (Its listing is omitted here.) The program employs the naive and the landmark strategies to issue several point-location queries on this arrangement.

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/point_location_example.cpp

Note that the program uses the locate_point() function template to locate a point and nicely print the result of each query; see here.

Another important query issued on arrangements is the vertical ray-shooting query: Given a query point, which arrangement feature do we encounter by a vertical ray shot upward (or downward) from this point? In the general case the ray hits an edge, but it is possible that it hits a vertex, or that the arrangement does not have any vertex or edge lying directly above (or below) the query point.

All point-location classes listed in the previous section are also models of the ArrangementVerticalRayShoot_2 concept. That is, they all have member functions called ray_shoot_up(q) and ray_shoot_down(q) that accept a query point q. These functions output an object of type type Arr_point_location_result<Arrangement_2>::Type—a discriminated union container of the bounded types Vertex_const_handle, Halfedge_const_handle, or Face_const_handle. The latter type is used for the unbounded face of the arrangement, in case there is no edge or vertex lying directly above (or below) q.

The function template vertical_ray_shooting_query() listed below accepts a vertical ray-shooting object, the type of which models the ArrangementVerticalRayShoot_2 concept. It exports the result of the upward vertical ray-shooting operation from a given query point to the standard output-stream. The ray-shooting object vrs is assumed to be already attached to an arrangement. The function template is defined in the header file `point_location_utils.h.

The program below uses the function template listed above to perform vertical ray-shooting queries on an arrangement. The arrangement and the query points are exactly the same as in point_location.cpp; see Figure 34.6.

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/vertical_ray_shooting.cpp

The number type we use in this example is CGAL's built-in MP_Float type, which is a floating-point number with an unbounded mantissa and a 32-bit exponent. It supports construction from an integer or from a machine float or double and performs additions, subtractions and multiplications in an exact number.

Suppose that at a given moment our application has to issue a relatively large number \( m\) of point-location queries on a specific arrangement object. Naturally, It is possible to define a point-location object and use it to issue separate queries on the arrangement. However, as explained in Section Point-Location Queries choosing a simple point-location strategy (either the naive or the walk strategy) means inefficient queries, while the more sophisticated strategies need to construct auxiliary structures that incur considerable overhead in running time.

Alternatively, the 2D Arrangement package includes a free locate() function that accepts an arrangement and a range of query points as its input and sweeps through the arrangement to locate all query points in one pass. The function outputs the query results as pairs, where each pair consists of a query point and a discriminated union container, which represents the cell containing the point; see Section Point-Location Queries. The output pairs are sorted in increasing $xy$-lexicographical order of the query point.

The batched point-location operation is carried out by sweeping the arrangement. Thus, it takes \( O((m+N)\log{(m+N)}) \) time, where \( N \) is the number of edges in the arrangement. Issuing separate queries exploiting a point-location strategy with logarithmic query time per query, such as the trapezoidal map RIC strategy (see Section Choosing a Point-Location Strategy), is asymptotically more efficient. However, experiments show that when the number \( m \) of point-location queries is of the same order of magnitude as \( N\), the batched point-location operation is more efficient in practice. One of the reasons for the inferior performance of the alternative (asymptotically faster) procedures is the necessity to construct and maintain complex additional data structures.

The program below issues a batched point-location query, which is essentially equivalent to the six separate queries performed in point_location_example.cpp; see Section Point-Location Queries.

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/batched_point_location.cpp

In Section The Main Arrangement Class we reviewed in details the Arrangement_2 class, which represents two-dimensional subdivisions induced by planar curves, and mentioned that its interface is minimal in the sense that the member functions hardly perform any geometric algorithms and are mainly used for maintaining the topological structure of the subdivision. In this section we explain how to utilize the free (global) functions that operate on arrangements. The implementation of these operations typically require non-trivial geometric algorithms or load some extra requirements on the traits class.

In Section The Main Arrangement Class we explained how to construct arrangements of \( x\)-monotone curves that are pairwise disjoint in their interior, when the location of the segment endpoints in the arrangement is known. Here we relax this constraint, and allow the location of the inserted \( x\)-monotone curve endpoints to be arbitrary, as it may be unknown at the time of insertion. We retain, for the moment, the requirement that the interior of the inserted curve is disjoint from all existing arrangement edges and vertices.

The free function insert_non_intersecting_curve(arr, c, pl) inserts the \( x\)-monotone curve \( c\) into the arrangement arr, with the precondition that the interior of \( c\) is disjoint from all arr's existing edges and vertices. The third argument pl is a point-location object attached to the arrangement, which is used for performing the insertion. It locates both curve endpoints in the arrangement, where each endpoint is expected to either coincide with an existing vertex or lie inside a face. It is possible to invoke one of the specialized insertion functions (see Section The Main Arrangement Class), based on the query results, and insert \( c\) at its proper position.The insert_non_intersecting_curve() function, as all other functions reviewed in this section, is a function template, parameterized by an arrangement class and a point-location class (a model of the ArrangementPointLocation_2 concept). The insertion operation thus hardly requires any geometric operations on top on the ones needed to answer the point-location queries. Moreover, it is sufficient that the arrangement class is instantiated with a traits class that models the ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept (or the ArrangementLandmarkTraits_2 concept, if the landmark point-location strategy is used), which does not have to support the computation of intersection points between curves.

The variant insert_non_intersecting_curve(arr, c) is also available. Instead of accepting a user-defined point-location object, it defines a local instance of the walk point-location class and uses it to insert the curve.

The insert_non_intersecting_curve() function is very efficient, but its preconditions on the input curves are still rather restricting. Let us assume that the arrangement is instantiated with a traits class that models the refined ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept and supports intersection computations (see Section Traits Classes for the exact details). Given an \( x\)-monotone curve, it is sufficient to locate its left endpoint in the arrangement and to trace its zone, namely the set of arrangement features crossing the curve, until the right endpoint is reached. Each time the new curve \( c\) crosses an existing vertex or an edge, the curve is split into subcurves (in the latter case, we have to split the curve associated with the existing halfedge as well) and associate new edges with the resulting subcurves. Recall that an edge is represented by a pair of twin halfedges, so we split it into two halfedge pairs.

The free function insert(arr, c, pl) performs this insertion operation. It accepts an \( x\)-monotone curve \( c\), which may intersect some of the curves already in the arrangement arr, and inserts it into the arrangement by computing its zone. Users may supply a point-location object pl, or use the default walk point-location strategy (namely, the variant insert(arr, c) is also available). The running-time of this insertion function is proportional to the complexity of the zone of the curve \( c\).

In some cases users may have a prior knowledge of the location of the left endpoint of the \( x\)-monotone curve c they wish to insert, so they can perform the insertion without issuing any point-location queries. This can be done by calling insert(arr, c, obj), where obj is an object represents the location of c's left endpoint in the arrangement - namely it wraps a Vertex_const_handle, a Halfedge_const_handle or a Face_const_handle (see also Section Point-Location Queries).

So far all our examples were of arrangements of line segments, where the Arrangement_2 template was instantiated with the Arr_segment_traits_2 class. In this case, the fact that insert() accepts an \( x\)-monotone curve does not seem to be a restriction, as all line segments are \( x\)-monotone (note that we consider vertical line segments to be weakly \( x\)-monotone).

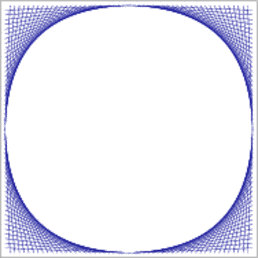

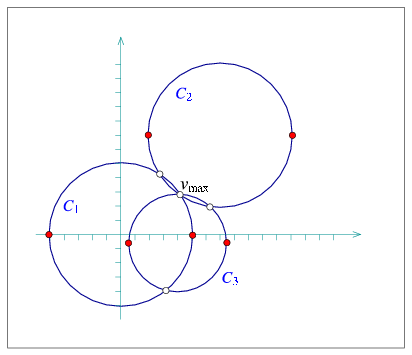

Suppose that we construct an arrangement of circles. A circle is obviously not \( x\)-monotone, so we cannot insert it in the same way we inserted \( x\)-monotone curves. Note that a key operation performed by insert() is to locate the left endpoint of the curve in the arrangement. A circle, however, does not have any endpoints! However, it is possible to subdivide each circle into two \( x\)-monotone circular arcs (its upper half and its lower half) and to insert each \( x\)-monotone arc separately.

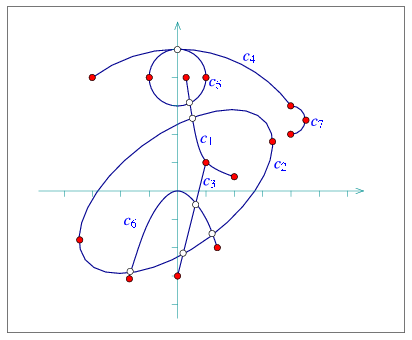

The free function insert() also supports general curve and not necessarily \( x\)-monotone curves. In this case it requires that the traits class used by the arrangement arr to be a model of the concept ArrangementTraits_2, which refines the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept. It has to define an additional Curve_2 type (which may differ from the X_monotone_curve_2 type), and support the subdivision of curves of this new type into \( x\)-monotone curves (see the exact details in Section Traits Classes). The insert(arr, c, pl) function performs the insertion of the curve \( c\), which does not need to be \( x\)-monotone, into the arrangement by subdividing it (if needed) into \( x\)-monotone subcurves and inserting each one separately. Users may supply a point-location object pl, or use the default walk point-location strategy by calling insert(arr, c).

The arrangement class enables us to insert a point as an isolated vertex in a given face. The free function insert_point(arr, p, pl) inserts a vertex into arr that corresponds to the point p at an arbitrary location. It uses the point-location object pl to locate the point in the arrangement (by default, the walk point-location strategy is used), and acts according to the result as follows:

p is located inside a face, it is inserted as an isolated vertex inside this face. p lies on an edge, the edge is split to create a vertex associated with p. p coincides with an existing vertex and we are done. In all cases, the function returns a handle to the vertex associated with p.

The arrangement arr should be instantiated with a traits class that models the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept, as the insertion operation may involve splitting curves.

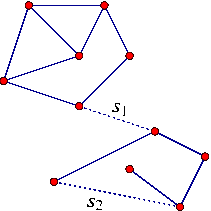

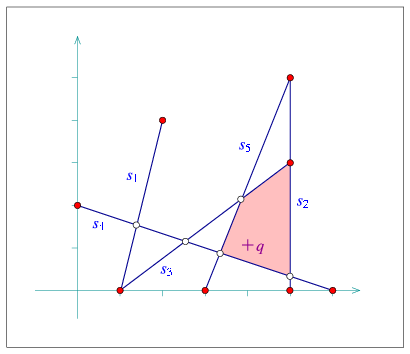

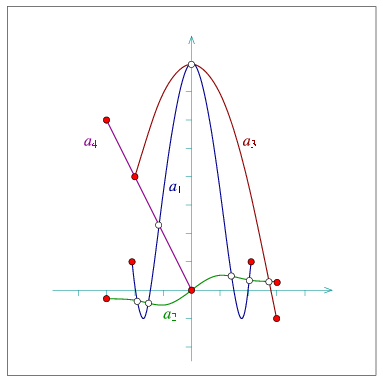

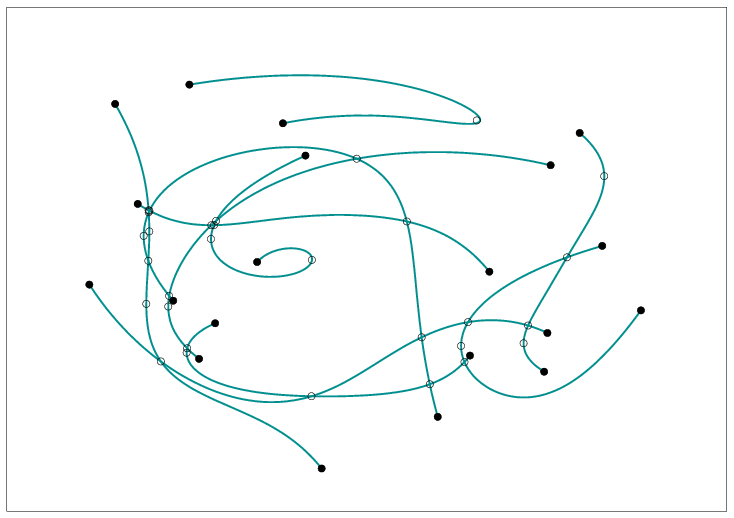

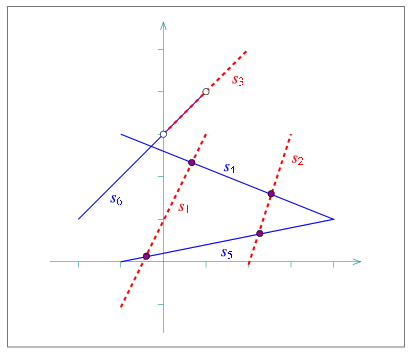

incremental_insertion.cpp and aggregated_insertion.cpp. The segment endpoints are marked by black disks and the arrangement vertices that correspond to intersection points are marked by circles. The query point \( q\) is marked with a cross and the face that contains it is shaded. The program below constructs an arrangement of intersecting line-segments. We know that \( s_1\) and \( s_2\) do not intersect, so we use insert_non_intersecting_curve() to insert them into the empty arrangement. The rest of the segments are inserted using insert(). The resulting arrangement consists of \( 13\) vertices, \( 16\) edges, and \( 5\) faces, as can be seen in Figure 34.7.

In the earlier examples, all arrangement vertices corresponded to segment endpoints. In this example we have additional vertices that correspond to intersection points between two segments. The coordinates of these intersection points are rational numbers, if the input coordinates are rational (or integer). Therefore, the Quotient<int> number type is used to represent the coordinates:

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/incremental_insertion.cpp

In this section we have described so far free functions that insert curves and points to a given arrangement. Now we will describe functions that don't insert curves or points to an arrangement nor do they change the arrangement, but they are closely related to the incremental insertion functions as they also use the zone algorithm.

The free function do_intersect() checks if a given curve or \( x\)-monotone curve intersects an existing arrangement's edges or vertices. If the give curve is not an \( x\)-monotone curve then the function subdivides the given curve into \( x\)-monotone subcurves and isolated vertices . Each subcurve is in turn checked for intersection. The function uses the zone algorithm to check if the curve intersects the arrangement. First, the curve's left endpoint is located. Then, its zone is computed starting from its left endpoint location. The zone computation terminates when an intersection with an arrangement's edge/vertex is found or when the right endpoint is reached. A given point-location object is used for locating the left endpoint of the given curve in the existing arrangement. By default, the function uses the "walk along line" point-location strategy - namely an instance of the class Arr_walk_along_line_point_location. If the given curve is \( x\)-monotone then the traits class must model the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept. If the curve is not \( x\)-monotone curve then the traits class must model the ArrangementTraits_2 concept.

The zone() function computes the zone of a given \( x\)-monotone curve in a given arrangement. Meaning, it outputs all the arrangement's elements (vertices, edges and faces) that the \( x\)-monotone curve intersects in the order that they are discovered when traversing the \( x\)-monotone curve from left to right. The function uses a given point-location object to locate the left endpoint of the given \( x\)-monotone curve. By default, the function uses the "walk along line" point-location strategy. The function requires that the traits class will model the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept.

Let us assume that we have to insert a set of \( m\) input curves into an arrangement. It is possible to do this incrementally, inserting the curves one by one, as shown in the previous section. However, the arrangement package provides three free functions that aggregately insert a range of curves into an arrangement:

insert_non_intersecting_curves(arr, begin, end) inserts a range of \( x\)-monotone curves given by the input iterators [begin, end) into an arrangement arr. The \( x\)-monotone curves should be pairwise disjoint in their interior and also interior-disjoint from all existing edges and vertices of arr. insert(arr, begin, end) inserts a range of general (not necessarily \( x\)-monotone) curves of type Curve_2 or X_monotone_curve_2 that may intersect one another, given by the input iterators [begin, end), into the arrangement arr. We distinguish between two cases: (i) The given arrangement arr is empty (has only an unbounded face), so we have to construct it from scratch. (ii) We have to insert \( m\) input curves to a non-empty arrangement arr.

In the first case, we sweep over the input curves, compute their intersection points and construct the Dcel that represents their planar arrangement. This process is performed in \( O\left((m + k)\log m\right)\) time, where \( k\) is the total number of intersection points. The running time is asymptotically better than the time needed for incremental insertion, if the arrangement is relatively sparse (when \( k\) is bounded by \( \frac{m^2}{\log m}\)), but in practice it is recommended to use this aggregated construction process even for dense arrangements, since the sweep-line algorithm needs less geometric operations compared to the incremental insertion algorithms and hence typically runs much faster in practice.

Another important advantage the aggregated insertion functions have is that they do not issue point-location queries. Thus, no point-location object needs to be attached to the arrangement. As explained in Section Point-Location Queries, there is a trade-off between construction time and query time in each of the point-location strategies, which affects the running times of the incremental insertion process. Naturally, this trade-off is irrelevant in case of aggregated insertion as above.

The example below shows how to construct the arrangement of line segments depicted in Figure 34.7 and built incrementally in incremental_insertion.cpp, as shown in the previous section. We use the aggregated insertion function insert() as we deal with line segments. Note that no point-location object needs to be defined and attached to the arrangement:

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/aggregated_insertion.cpp

In case we have to insert a set of \( m\) curves into an existing arrangement, where we denote the number of edges in the arrangement by \( N\). As a rule of thumb, if \( m = o(\sqrt{N})\), we insert the curves one by one. For larger input sets, we use the aggregated insertion procedures.

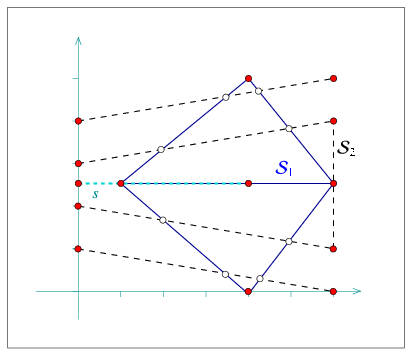

global_insertion.cpp. The segments of \( {\mathcal S}_1\) are drawn in solid lines and the segments of \( {\mathcal S}_2\) are drawn in dark dashed lines. Note that the segment \( s\) (light dashed line) overlaps one of the segments in \( {\mathcal S}_1\). In the example below we aggregately construct an arrangement of a set \( {\mathcal S}_1\) containing five line segments. Then we insert a single segment using the incremental insertion function. Finally, we add a set \( {\mathcal S}_2\) with five more line segments in an aggregated fashion. Notice that the line segments of \( {\mathcal S}_1\) are pairwise interior-disjoint, so we use insert_non_intersecting_curves(). \( {\mathcal S}_2\) also contain pairwise interior-disjoint segments, but as they intersect the existing arrangement, we have to use insert() to insert them. Also note that the single segment \( s\) we insert incrementally overlaps an existing arrangement edge:

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/global_insertion.cpp

The number type used in the example above, Quotient<MP_Float>, is comprised of a numerator and a denominator of type MP_Float, namely floating-point numbers with unbounded mantissa. This number type is therefore capable of exactly computing the intersection points as long as the segment endpoints are given as floating-point numbers.

The free functions remove_vertex() and remove_edge() handle the removal of vertices and edges from an arrangement. The difference between these functions and the member functions of the Arrangement_2 template having the same name is that they allow the merger of two curves associated with adjacent edges to form a single edge. Thus, they require that the traits class that instantiates the arrangement instance is a model of the refined ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept (see Section Traits Classes).

The function remove_vertex(arr, v) removes the vertex v from the given arrangement arr, where v is either an isolated vertex or is a redundant vertex - namely, it has exactly two incident edges that are associated with two curves that can be merged to form a single \( x\)-monotone curve. If neither of the two cases apply, the function returns an indication that it has failed to remove the vertex.

The function remove_edge(arr, e) removes the edge e from the arrangement by simply calling arr.remove_edge(e) (see Section Modifying the Arrangement). In addition, if either of the end vertices of e becomes isolated or redundant after the removal of the edge, it is removed as well.

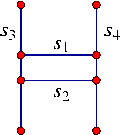

The following example demonstrates the usage of the free removal functions. It creates an arrangement of four line segment forming an H-shape with a double horizontal line. Then it removes the two horizontal edges and clears all redundant vertices, such that the final arrangement consists of just two edges associated with the vertical line segments:

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/global_removal.cpp

Previous sections dealt only with arrangements of line segments, namely of bounded curves. Such arrangements always have one unbounded face that contains all other arrangement features. This section explains how to construct arrangements of unbounded curves, such as lines and rays.

Consider the arrangement induced by the two lines \( y = x\) and \( y = -x\). These two lines intersect at the origin, such that the arrangement contains a single vertex \( v = (0,0)\), with four infinite rays emanating from it. Each ray corresponds to an arrangement edge, and these edges subdivide the plane into four unbounded faces. Consider a halfedge pair that represents one of the edges. The source vertex of one of these halfedges is \( v\) and its target is at infinity, while the other has its source at infinity and \( v\) is its target.

If e is an object of the nested type Arrangement_2::Halfedge, then the predicates e.source_at_infinity() and e.target_at_infinity() indicate whether the halfedge represents a curve with an infinite end. In general there is no need to access the source (or the target) of a halfedge if it lies at infinity, since this vertex is not associated with any valid point. Similarly, calling arr.number_of_vertices() for an arrangement object arr counts only the vertices associated with finite points, and ignores vertices at infinity (and the range [vertices_begin(), vertices_end()) contains only finite vertices). The method arr.number_of_vertices_at_infinity() counts the number of vertices at infinity.

As mentioned above, arrangements of unbounded curves usually have more than one unbounded face. The function arr.number_of_unbounded_faces() returns the number of unbounded arrangement faces (Thus, arr.number_of_faces() - arr.number_of_unbounded_faces() is the number of bounded faces). The functions arr.unbounded_faces_begin() and arr.unbounded_faces_end() return iterators of type Arrangement_2::Unbounded_face_iterator that specify the range of unbounded faces. Naturally, the value-type of this iterator is Arrangement_2::Face.

The specialized insertion functions listed in Section Inserting Non-Intersecting x-Monotone Curves can also be used for inserting \( x\)-monotone unbounded curves, provided that they are interior-disjoint from any subcurve that already exists in the arrangement. For example, if you wish to insert a ray \( r\) emanating from \( (0,0)\) in the direction of \( (1,0)\), to the arrangement of \( y = -x\) and \( y = x\), you can use the function arr.insert_from_left_vertex(), as the left endpoint of \( r\) is already associated with an arrangement vertex. Other edge-manipulation functions can also be applied on edges associated with unbounded curves.

The following example demonstrates the use of the insertion function for pairwise interior-disjoint unbounded curves. In this example we use the traits class Arr_linear_traits_2<Kernel> to instantiate the Arrangement_2 template. This traits class is capable of representing line segments as well as unbounded linear curves (namely lines and rays). Observe that objects of the type X_monotone_curve_2 defined by this traits class are constructible from Line_2, Ray_2, and Segment_2 objects, as defined in the instantiated kernel.

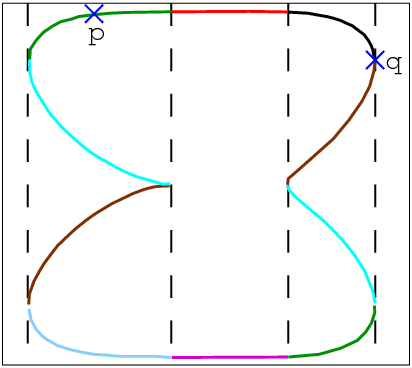

The first three curves are inserted using the special insertion functions for \( x\)-monotone curves whose location in the arrangement is known. Notice that inserting an unbounded curve in the interior of an unbounded face, or from an existing vertex that represents the bounded end of the curve, may cause an unbounded face to split (this is never the case when inserting a bounded curve - compare with Section Inserting Non-Intersecting x-Monotone Curves). Then, three additional rays are inserted incrementally, using the insertion function for \( x\)-monotone curves whose interior is disjoint from all arrangement features. Finally, the program prints the size of the arrangement (compare to the illustration in Figure 34.9) and the outer boundaries of its six unbounded faces:

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/unbounded_non_intersecting.cpp

In principle, all queries and operations that relate to arrangements of bounded curves can also be applied to arrangements of unbounded curves. For example, it is possible to issue point-location and vertical ray-shooting queries (see also Section Issuing Queries on an Arrangement) on arrangements of lines, where the only restriction is that the query point has finite coordinates.Currently, all point-location strategies except the trapezoidal RIC point-location strategy are capable of handling arrangements of unbounded curves.

In the following example we show how an arrangement of unbounded lines is utilized to solve the following problem: Given a set of points, does the set contain at least three collinear points? In this example a set of input points is read from a file. The file points.dat is used by default. It contains definitions of \( 100\) points randomly selected on the grid \( [-10000,10000]\times[-10000,10000]\). We construct an arrangement of the dual lines, where the line \( p^{*}\) dual to the point \( p = (p_x, p_y)\) is given by the equation \( y = p_x*x - p_y\), and check whether three (or more) of the dual lines intersect at a common point, by searching for a (dual) vertex, whose degree is greater than \( 4\). If such a vertex exists, then there are at least three dual lines that intersect at a common point, which implies that there are at least three collinear points.

File Arrangement_on_surface_2/dual_lines.cpp

Note that there are no three collinear points among the points defined in the input file points.dat. In the second part of the example the existence of collinearity is forced and verified as follows. A line dual to the midpoint of two randomly selected points is introduced, and inserted into the arrangement. This operation is followed by a test that verifies that a vertex of degree greater than \( 4\) exists. This implied that collinearity indeed exists as explained above.

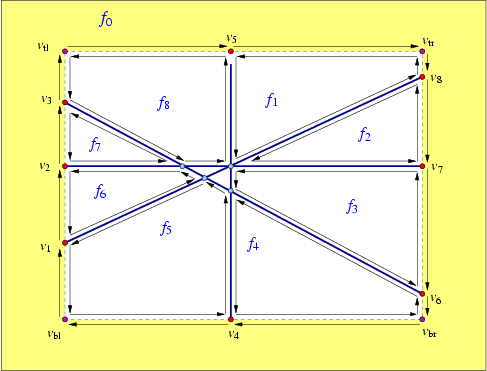

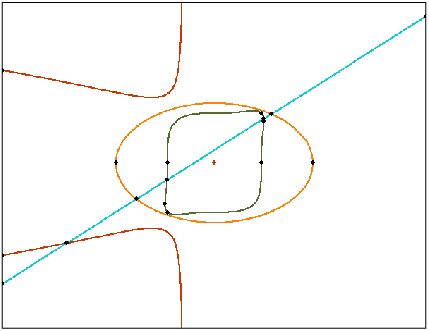

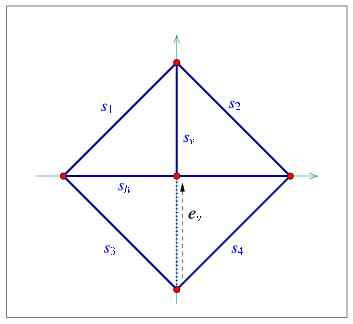

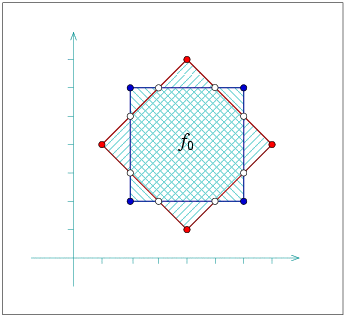

Given a set \( \cal C\) of unbounded curves, a simple approach for representing the arrangement induced by \( \cal C\) would be to clip the unbounded curves using an axis-parallel rectangle that contains all finite curve endpoints and intersection points between curves in \( \cal C\). This process would result in a set \( \cal C\) of bounded curves (line segments if \( \cal C\) contains lines and rays), and it would be straightforward to compute the arrangement induced by this set. However, we would like to operate directly on the unbounded curves without having to preprocess them. Therefore, we use an implicit bounding rectangle embedded in the Dcel structure. Figure 34.10 shows the arrangement of four lines that subdivide the plane into eight unbounded faces and two bounded ones. Notice that in this case the unbounded faces have outer boundaries, and the halfedges along these outer CCBs are drawn as arrows. The bounding rectangle is drawn with a dashed line. The vertices \( v_1,v_2,\ldots,v_8\), which represent the unbounded ends of the four lines, and lie on the bounding rectangle, actually exist at infinity, and the halfedges connecting them are fictitious, and represent portions of the bounding rectangle. Note that the outer CCBs of the unbounded faces contain fictitious halfedges. The twins of these halfedges form together one connected component that corresponds to the entire bounding rectangle, which forms a single hole in a face \( f_0\). We say that \( f_0\) is fictitious, as it does not correspond to a real two-dimensional cell of the arrangement.

Observe that there are four extra vertices at infinity that do not lie on any curve; they are denoted as \( v_{\rm bl}, v_{\rm tl}, v_{\rm br}\), and \( v_{\rm tr}\), and represent the bottom-left, top-left, bottom-right, and top-right corners of the bounding rectangle, respectively. Similarly, there are fictitious halfedges that lie on the top, the bottom, the left, or the right edge of the bounding rectangle. When the arrangement is empty, there are exactly four pairs of fictitious halfedges, that divide the plane into two faces, namely a fictitious face lying outside of the bounding rectangle and a single unbounded face bounded by the bounding rectangle.

Summarizing the above, there are four types of arrangement vertices, which differ from one another by their location with respect to the bounding bounding rectangle:

A vertex (at infinity) of Type typeunbounded or Type typeunboundedvertical above always has three incident edges: one concrete edge that is associated with an unbounded portion of an \( x\)-monotone curve, and two fictitious edges connecting the vertex to its neighboring vertices at infinity. Fictitious vertices (of type 4 above) have exactly two incident edges. See Section Traits Classes on how the traits-class interface helps imposing the fact that we never have more than one curve incident to any true vertex at infinity.

The nested types defined in the Arrangement_2 class support the following methods, in addition to the ones listed in Section Traversing the Arrangement :

Vertex class provides three-valued predicates parameter_space_in_x() and parameter_space_in_y(), which return the location of the geometric embedding of the vertex in the parameter space. In particular, the former returns ARR_LEFT_BOUNDARY, ARR_INTERIOR, or ARR_RIGHT_BOUNDARY, and the latter returns ARR_BOTTOM_BOUNDARY, ARR_INTERIOR, or ARR_TOP_BOUNDARY. As the package currently supports only the case where the parameter space is the compactified plane, the former returns ARR_INTERIOR if the \( x\)-coordinate associated with the vertex is finite, ARR_LEFT_BOUNDARY if it is \( -\infty\), and ARR_RIGHT_BOUNDARY if it is \( \infty\). The latter returns ARR_INTERIOR if the \( y\)-coordinate associated with the vertex is finite, ARR_BOTTOM_BOUNDARY if it is \( -\infty\), and ARR_TOP_BOUNDARY if it is \( \infty\). The Boolean predicate is_at_open_boundary() is also provided. You can access the point associated with a vertex only if it is not a vertex at an open boundary (recall that a vertex at an open boundary is not associated with a Point_2 object). Halfedge class provides the Boolean predicate is_fictitious(). The \( x\)-monotone curve associated with a halfedge can be accessed by the curve() method only if the halfedge is not fictitious. Face class provides the Boolean predicate f.is_fictitious(). The method outer_ccb() has the precondition that the face is not fictitious. Note that non-fictitious unbounded faces always have valid CCBs (although this CCB may comprise only fictitious halfedge in case the arrangement contains only bounded curves). The method arr.number_of_edges() does not count the number of fictitious edges, (which is always arr.number_of_vertices_at_infinity() + 4), and the iterators returned by arr.edges_begin() and arr.edges_end() specify a range of non-fictitious edges. Similarly, arr.number_of_faces() does not count the fictitious face. However, the Ccb_halfedge_circulator of the outer boundary of an unbounded face or the Halfegde_around_vertex_circulator of a vertex at infinity do traverse fictitious halfedges. For example, it is possible to traverse the outer boundaries of the unbounded arrangement edges using the following procedure:

As mentioned in the introduction of this chapter, the traits class encapsulates the definitions of the geometric entities and implements the geometric predicates and constructions needed by the Arrangement_2 class and by its peripheral algorithms. We also mention throughout the chapter that there are different levels of requirements from the traits class, namely the traits class can model different concept refinement-levels.

A model of the basic concept, ArrangementBasicTraits_2, needs to define the types Point_2 and X_monotone_curve_2, where objects of the first type are the geometric mapping of arrangement vertices, and objects of the latter type are the geometric mapping of edges. Such a model has to support in addition the following set of operations:

Compare_x_2:Compare_xy_2:Construct_min_vertex_2,Construct_max_vertex_2:Compare_y_at_x_2:Compare_y_at_x_right_2:Equal_2:Is_vertical_2:Each model of the concept ArrangementBasicTraits_2 needs to define a tag named Has_left_category. It determines whether the traits class supports the following predicate:

Compare_y_at_x_left_2:This predicate is optional, as it can be answered using the other traits-class primitives, and we wish to alleviate the need to implement an extra method that is not absolutely necessary. However, as implementing the predicate directly may prove to be more efficient, the traits-class implementer may choose to provide it.

The basic set of predicates is sufficient for constructing arrangements of \( x\)-monotone curves that do not reach or approach the boundary of the parameter space. The nature of the input curves, i.e., whether some of them are expected to reach or approach the left, right, bottom, or top side of the boundary of the parameter space, must be conveyed by the traits class. This is done through the definition of four additional nested types, namely Left_side_category, Right_side_category, Bottom_side_category, and Top_side_category. Each of those types must be convertible to the type Arr_oblivious_side_tag for the class to be a model of the concept ArrangementBasicTraits_2.

The type of an arrangement associated with the landmark point-location strategy (see Section Point-Location Queries) must be an instance of the Arrangement_2<Traits,Dcel> class template, where the Traits parameter is substituted with a model of the concept ArrangementLandmarkTraits_2. (Naturally, it can also model either the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept or the ArrangementTraits_2 concept.) The ArrangementLandmarkTraits_2 concept refines the two concepts ArrangementApproximateTraits_2 and ArrangementConstructXMonotoneCurveTraits_2. Each of these two concepts, in turn, refines the concept ArrangementBasicTraits_2.

A model of the ArrangementApproximateTraits_2 concept must define a fixed precision number type (typically the double-precision floating-point double) and support the additional below (in addition to fulfilling the requirements listed by the ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept).

Approximate_2: p, approximate the \( x\) and \( y\)-coordinates of p using the fixed precision number type. We use this operation for approximate computations—there are certain operations in the search for the location of the point that need not be exact and we can perform them faster than other operations. A model of the ArrangementConstructXMonotoneCurveTraits_2 concept support the operation below (in addition to fulfilling the requirements listed by the ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept).

Construct_x_monotone_curve_2: A traits class that models the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept, which refines the ArrangementBasicTraits_2 concept, has to support the following functions:

Intersection_2:Split_2:Are_mergeable_2:Merge_2:Using a model of the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2, it is possible to construct arrangements of sets of \( x\)-monotone curves (and points) that may intersect one another.

The concept ArrangementTraits_2 refines the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept by adding the notion of a general, not necessarily \( x\)-monotone (and not necessarily continuous) curve. A model of this concept must define the Curve_2 type and support the subdivision of a curve into a set of continuous \( x\)-monotone curves and isolated points using the predicate Make_x_monotone_2. For example, the curve \( C:\ (x^2 + y^2)(x^2 + y^2 - 1) = 0\) is the unit circle (the loci of all points for which \( x^2 + y^2 = 1\)) with the origin \( (0,0)\) as a singular point in its interior. \( C\) should therefore be divided into two circular arcs (the upper part and the lower part of the unit circle) and a single isolated point.

Note that the refined model ArrangementTraits_2 is required only when using the free insert() functions (see Section Free Functions in the Arrangement Package), which accept a Curve_2 object in the incremental version, or a range of Curve_2 objects in the aggregated version. In all other cases it is sufficient to use a model of the ArrangementXMonotoneTraits_2 concept.

An arrangement that supports unbounded \( x\)-monotone curves maintains an implicit bounding rectangle in the Dcel structure; see Section Representation of Unbounded Arrangements. The unbounded ends of vertical rays, vertical lines, and curves with vertical asymptotes are represented by vertices that lie on the bottom or top sides of this bounding rectangle. These vertices are not associated with points, but are associated with (finite) \( x\)-coordinates. The unbounded ends of all other curves are represented by vertices that lie on the left or right sides of this bounding rectangle. These vertices are not associated with points either. Edges connect these vertices and the four vertices that represents the corners of this bounding rectangle to form the rectangle.

Several predicates are required to handle \( x\)-monotone curves that approach infinity and thus approach the boundary of the parameter space. These predicates are sufficient to handle not only curves embedded in an unbounded parameter space, but also curves embedded in a bounded parameter space with open boundaries. Let \( b_l\) and \( b_r\) denote the \( x\)-coordinates of the left and right boundaries of the parameter space, respectively. Let \( b_b\) and \( b_t\) denote the \( y\)-coordinates of the bottom and top boundaries of the parameter space, respectively. Recall that currently the general code of the arrangement only supports the case where the parameter space is the entire compactified plane, thus \( b_l = b_b = -\infty\) and \( b_r = b_t = +\infty\). Nonetheless, when the parameter space is bounded, it is the exact geometric embedding of the implicit bounding rectangle. In the following we assume that an \( x\) monotone curve \( C\) can be considered as a parametric curve \( C(t) = (X(t),Y(t))\) defined over a closed, open, or half open interval with endpoints \( 0\) and \( 1\).

Models of the concept ArrangementOpenBoundaryTraits_2 handle curves that approach the boundary of the parameter space. This concept refines the concept ArrangementBasicTraits_2. The arrangement template instantiated with a traits class that models this concept can handle curves that are unbounded in any direction. If some curves inserted into an arrangement object are expected to be unbounded, namely, there exists \( d \in \{0,1\}\) such that \( \lim_{t \rightarrow d}X(t) = \pm\infty\) or \( \lim_{t \rightarrow d}y(t) = \pm\infty\) holds for at least one input curve \( C(t) = (X(t),Y(t))\), the arrangement template must be instantiated with a model of the ArrangementOpenBoundaryTraits concept.We intend to enhance the arrangement template to handle curves confined to a bounded yet open parameter space. A curve that reaches the boundary of the parameter space in this case is bounded and open.