|

CGAL 5.5.2 - Triangulated Surface Mesh Simplification

|

|

CGAL 5.5.2 - Triangulated Surface Mesh Simplification

|

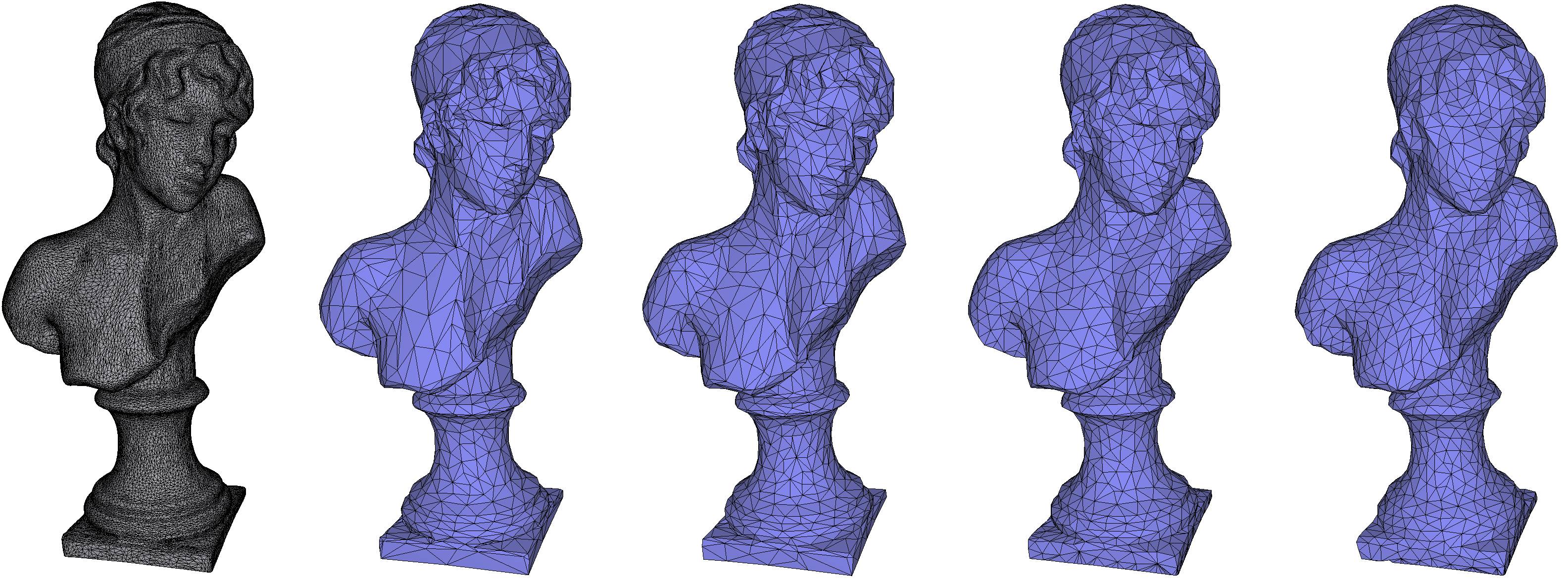

Surface mesh simplification is the process of reducing the number of faces used in a surface mesh while keeping the overall shape, volume and boundaries preserved as much as possible. It is the opposite of subdivision.

The algorithm presented here can simplify any oriented 2-manifold surface, with any number of connected components, with or without boundaries (border or holes) and handles (arbitrary genus), using a method known as edge collapse. Roughly speaking, the method consists of iteratively replacing an edge with a single vertex, removing 2 triangles per collapse.

Edges are collapsed according to a priority given by a user-supplied cost function, and the coordinates of the replacing vertex are determined by another user-supplied placement function. The algorithm terminates when a user-supplied stop predicate is met, such as reaching the desired number of edges.

The algorithm implemented here is generic in the sense that it does not require the surface mesh to be of a particular type but to be a model of the MutableFaceGraph and HalfedgeListGraph concepts. We give examples for Surface_mesh, Polyhedron_3, and OpenMesh.

The design is policy-based (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Policy-based_design), meaning that you can customize some aspects of the process by passing a set of policy objects. Each policy object specifies a particular aspect of the algorithm, such as how edges are selected and where the replacement vertex is placed. All policies have a sensible default. Furthermore, the API uses the so-called named-parameters technique which allows you to pass only the relevant parameters, in any order, omitting those parameters whose default is appropriate.

The free function that implements the simplification algorithm takes not only the surface mesh and the desired stop predicate but a number of additional parameters which control and monitor the simplification process. This section briefly describes the process in order to set the background for the discussion of the parameters to the algorithm.

There are two slightly different "edge" collapse operations. One is known as edge-collapse while the other is known as halfedge-collapse. Given an edge e joining vertices w and v, the edge-collapse operation replaces e,w and v for a new vertex r, while the halfedge-collapse operation pulls v into w, eliminating e and leaving w in place. In both cases the operation removes the edge e along with the 2 triangles adjacent to it.

This package uses the halfedge-collapse operation, which is implemented by removing, additionally, 1 vertex (v) and 2 edges, one per adjacent triangle. It optionally moves the remaining vertex (w) into a new position, called placement, in which case the net effect is the same as in the edge-collapse operation.

Naturally, the surface mesh that results from an edge collapse deviates from the initial surface mesh by some amount, and since the goal of simplification is to reduce the number of triangles while retaining the overall look of the surface mesh as much as possible, it is necessary to measure such a deviation. Some methods attempt to measure the total deviation from the initial surface mesh to the completely simplified surface mesh, for example, by tracking an accumulated error while keeping a history of the simplification changes. Other methods, like the ones implemented in this package, attempt to measure only the cost of each individual edge collapse (the local deviation introduced by a single simplification step) and plan the entire process as a sequence of steps of increasing cost.

Global error tracking methods produce highly accurate simplifications but take up a lot of additional space. Cost-driven methods, like the ones in this package, produce slightly less accurate simplifications but take up much less additional space, even none in some cases.

This package provides two cost-driven methods. The first cost-driven method implemented in this package, namely Lindstrom&Turk, is mainly based on [4], [5], with contributions from [3], [2] and [1]. The second cost-driven method implemented in this package, namely Garland&Heckbert, is mainly based on [2], with enhancements from Trettner and Kobbelt [7].

The algorithm proceeds in two stages. In the first stage, called collection stage, an initial collapse cost is assigned to each and every edge in the surface mesh. Then in the second stage, called collapsing stage, edges are processed in order of increasing cost. Some processed edges are collapsed while some are just discarded. Collapsed edges are replaced by a vertex and the collapse cost of all the edges now incident on the replacement vertex is recalculated, affecting the order of the remaining unprocessed edges.

Not all edges selected for processing are collapsed. A processed edge can be discarded right away, without being collapsed, if it does not satisfy certain topological and geometric conditions.

The algorithm presented in [2] contracts (collapses) arbitrary vertex pairs and not only edges by considering certain vertex pairs as forming a pseudo-edge and proceeding to collapse both edges and pseudo-edges in the same way as in [4], [5]. However, contracting an arbitrary vertex-pair may result in a non-manifold surface mesh, but the current state of this package can only deal with manifold surface meshes, thus, it can only collapse edges. That is, this package cannot be used as a framework for vertex contraction. Therefore, our implementation of [2] only collapses edges.

The specific way in which the collapse cost and vertex placement is calculated is called the cost strategy. The user can choose different strategies in the form of policies and related parameters, passed to the algorithm.

The current version of the package provides a set of policies implementing three strategies: the Lindstrom-Turk strategy, which is the default, the Garland-Heckbert family of strategies, and a strategy consisting of an edge-length cost with an optional midpoint placement (much faster but less accurate).

The main characteristic of the strategy presented in [4], [5] is that the simplified surface mesh is not compared at each step with the original surface mesh (or the surface mesh at a previous step) so there is no need to keep extra information, such as the original surface mesh or a history of the local changes. Hence the name memoryless simplification.

At each step, all remaining edges are potential candidates for collapsing and the one with the lowest cost is selected. The cost of collapsing an edge is given by the position chosen for the vertex that replaces it.

The replacement vertex position is computed as the solution to a system of 3 linearly-independent linear equality constraints. Each constraint is obtained by minimizing a quadratic objective function subject to the previously computed constraints. There are several possible candidate constraints and each is considered in order of importance. A candidate constraint might be incompatible with the previously accepted constraints, in which case it is rejected and the next constraint is considered. Once 3 constraints have been accepted, the system is solved for the vertex position. The first constraints considered preserves the shape of the surface mesh boundaries (in case the edge profile has boundary edges). The next constraints preserve the total volume of the surface mesh. The next constraints, if needed, optimize the local changes in volume and boundary shape. Lastly, if a constraint is still needed (because the ones previously computed were incompatible), a third (and last) constraint is added to favor equilateral triangles over elongated triangles.

The cost is then a weighted sum of the shape, volume and boundary optimization terms, where the user specifies the unit weighting unit factor for each term.

The local changes are computed independently for each edge using only the triangles currently adjacent to it at the time when the edge is about to be collapsed, that is, after all previous collapses. Thus, the transitive path of minimal local changes yields at the end a global change reasonably close to the absolute minimum.

As in the case of the Lindstrom-Turk strategy, the Garland-Heckbert strategy introduced in [2] does not compare the resulting mesh with the original mesh and does not depend on an history of local changes. Instead, it encodes approximate distance to the original mesh by using quadric matrices that it assigns to each vertex.

In its classic version, a quadric matrix \( Q \) is assigned to each vertex \( v \) and encodes the total squared distance that any point \( p \) has to \( v \)'s neighboring faces, which is given by the matrix product \( p'Qp \). At each step, the edge which minimizes the cost of collapsing is selected for the collapse operation. The cost of collapsing an edge is calculated by minimizing the error function \( p'Qp \) where \( Q \) is the combined quadric matrices of the edge's endpoints and \( p \) is the point that minimizes the cost (i.e., decision variables). The point \( p \) that minimizes the objective function is picked as the new placement point. Since the error function is quadratic, finding its minimum can be done by simply calculating the gradient and equating it to zero. If this fails due to a singularity, the optimal point and the cost are found on the edge. After placing the new vertex, a new quadric matrix is assigned to it by simply summing the quadric matrices of the two extremities of the edge that has been collapsed. Additional pseudo-faces that are perpendicular to neighboring faces are added to quadric matrices of border vertices in order to preserve sharp borders of the mesh as much as possible.

An extension of the Garland-Heckbert was proposed by Trettner and Kobbelt [7], who proposed the concept of probabilistic quadrics. In this new approach, the energy minimization is no longer performed using distances to input planes or polygons as in the classic version; instead, input geometry is made uncertain by introducing Gaussian noise in the input (vertex positions and face normals). This variance naturally deteriorates the tightness of the result, but on the other hand it enables creating more uniform triangulations and the approach is more tolerant to noise, while still maintaining feature sensitivity.

The cost strategy used by the algorithm is selected by means of three policies: GetPlacement, GetCost, and Filter.

The GetPlacement policy is called to compute the new position for the remaining vertex after the halfedge-collapse. It returns an optional value, which can be absent if the edge should not be collapsed.

The GetCost policy is called to compute the cost of collapsing an edge. This policy uses the placement to compute the cost (which is an error measure) and determines the ordering of the edges.

The algorithm maintains an internal data structure (a mutable priority queue) which allows each edge to be processed in increasing cost order. Such a data structure requires some per-edge additional information, such as the edge's cost. If the record of per-edge additional information occupies N bytes of storage, simplifying a surface mesh of 1 million edges (a normal size) requires 1 million times N bytes of additional storage. Thus, to minimize the amount of additional memory required to simplify a surface mesh only the cost is attached to each edge and nothing else.

But this is a trade-off: the cost of a collapse is a function of the placement (the new position chosen for the remaining vertex) so before GetCost is called for each and every edge, GetPlacement must also be called to obtain the placement parameter to the cost function. But that placement, which is a 3D point, is not attached to each and every edge since that would easily triple the additional storage requirement. On the one hand, this dramatically saves on memory but on the other hand is a processing waste because when an edge is effectively collapsed, GetPlacement must be called again to know were to move the remaining vertex.

Earlier prototypes showed that attaching the placement to the edge, thus avoiding one redundant call to the placement function after the edge collapsed, has little impact on the total running time. This is because the cost of an each edge is not just computed once but changes several times during the process so the placement function must be called several times just as well. Caching the placement can only avoid the very last call, when the edge is collapsed, but not all the previous calls which are needed because the placement (and cost) changes.

Finally, we explain the PlacementFilter policy. While the cost is a scalar that is used in the priority queue, there may be additional criteria coming in to decide if the edge collapse shall be performed or not. While such a criterion could be easily integrated into the cost function, that is setting the cost to infinity in order not to be considered a candidate for a collapse, we test a criterion only for an edge when it is the next edge to collapse. This makes the mesh simplification faster in case the computation of the criterion is expensive, for example when we check if the simplified mesh is in a tolerance envelope of the input mesh.

Since the algorithm is free from robustness issues there is no need for exact predicates nor constructions and Simple_cartesian<double> can be used safely. In the current version, 3.3, the LindstromTurk policies are not implemented for homogeneous coordinates, so a Cartesian kernel must be used.

The simplification algorithm is implemented as the free template function Surface_mesh_simplification::edge_collapse(). The function has two mandatory and several optional parameters.

There are two main parameters to the algorithm: the surface mesh to be simplified (in-place) and the stop predicate.

The surface mesh to simplify must be a model of the MutableFaceGraph and HalfedgeListGraph concepts.

The stop predicate is called after each edge is selected for processing, before it is classified as collapsible or not (thus before it is collapsed). If the stop predicate returns true the algorithm terminates.

The notion of named parameters was also introduced in the BGL. You can read about it in [6] or the following site: https://www.boost.org/libs/graph/doc/bgl_named_params.html. Named parameters allow the user to specify only those parameters which are really needed, by name, making the parameter ordering unimportant.

Say there is a function f() that takes 3 parameters called name, age and gender, and you have variables n,a and g to pass as parameters to that function. Without named parameters, you would call it like this: f(n,a,g), but with named parameters, you call it like this: f(name(n).age(a).gender(g)).

That is, you give each parameter a name by wrapping it into a function whose name matches that of the parameter. The entire list of named parameters is really a composition of function calls separated by a dot ( \( .\)). Thus, if the function takes a mix of mandatory and named parameters, you use a comma to separate the last non-named parameter from the first named parameters, like this:

f(non_named_par0, non_named_pa1, name(n).age(a).gender(g))

When you use named parameters, the ordering is irrelevant, so this: f(name(n).age(a).gender(g)) is equivalent to this: f(age(a).gender(g).name(n)), and you can just omit any named parameter that has a default value.

The following example illustrates the simplification of a Surface_mesh. The unspecified cost strategy defaults to Lindstrom-Turk.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_surface_mesh.cpp

The following example illustrates the simplification of a Polyhedron_3 with default vertices, halfedges, and faces. The unspecified cost strategy defaults to Lindstrom-Turk.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_polyhedron.cpp

The following example is equivalent to the previous example but using an enriched polyhedron whose halfedges support an id field to store the edge index needed by the algorithm.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_enriched_polyhedron.cpp

The following example shows how the mesh simplification package can be applied on a mesh data structure which is not part of CGAL, but a model of FaceGraph.

What is particular in this example is the property map that allows to associate 3D CGAL points to the vertices.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_OpenMesh.cpp

The following example shows how to use the optional named parameter edge_is_constrained_map to prevent edges from being removed. Edges marked as constrained are guaranteed to be in the final surface mesh. However, the vertices of the constrained edges may change and the placement may change the points. The wrapper CGAL::Surface_mesh_simplification::Constrained_placement guarantees that these points are not changed.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_constrained_border_surface_mesh.cpp

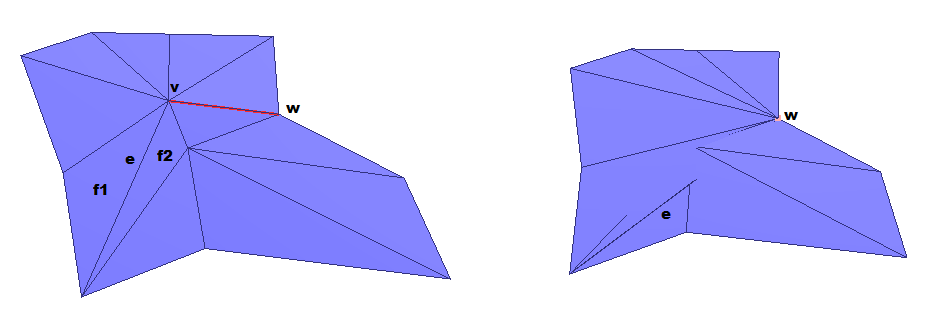

The surface mesh simplification does not guarantee that the resulting surface has no self intersections. Even the rather trivial mesh shown in Figure 70.2 results in a self intersection when one edge is collapsed using the Lindstrom-Turk method.

v-w into vertex w. While the normals of f1 and f2 are almost equal, they are opposed after the edge collapse. The class Surface_mesh_simplification::Bounded_normal_change_filter checks if a placement would invert the normal of a face around the stars of the two vertices of an edge that is candidate for an edge collapse. It then rejects this placement by returning boost::none.

Surface_mesh_simplification::Bounded_normal_change_placement. Using the filter is faster as it is only performed on the edge to be collapsed next, and not during the update of all edges incident to the vertex that is the result of the edge collapse.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_bounded_normal_change.cpp

The surface mesh simplification can be done in a way that the simplified mesh stays inside an envelope of the input mesh. This makes use of the class Polyhedral_envelope which enables to check whether a query point, segment, or triangle lies within a polyhedral envelope, which consists of the union of inflated triangles. While the user gives a tolerance \(\epsilon\), the check is conservative, that is there may be triangles which would be inside a surface obtained as the Minkowski sum envelope with a sphere of radius \(\epsilon\), but which are outside the polyhedral envelope.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_envelope.cpp

The last example shows how to use a visitor with callbacks that are called at the different steps of the simplification algorithm.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_visitor_surface_mesh.cpp

Each Garland-Heckbert simplification strategy is implemented with a single class that regroups both the cost and the placement policies, which must be used together as they share vertex quadric data. The classic strategy of using plane-based quadric error metrics is implemented with the class Surface_mesh_simplification::GarlandHeckbert_plane_policies. Although both policies must be used together, it is still possible to wrap either policy using behavior modifiers such as Surface_mesh_simplification::Bounded_normal_change_placement.

File Surface_mesh_simplification/edge_collapse_garland_heckbert.cpp

Note that these policies depend on the third party Eigen library.

The core of the package, as well as most of the simplification strategies, are the work of Fernando Cacciola, betwen 2006 and 2009.

Andreas Fabri added the Surface_mesh_simplification::Bounded_normal_change_placement functionality in CGAL 4.11.

The implementation of the Garland-Heckbert simplification policies is the result of the work of Baskın Şenbaşlar (Google Summer of Code 2019), and Julian Komaromy (Google Summer of Code 2021) They both were mentored by Mael Rouxel-Labbé, who also contributed to the code and to the documentation.