61.1 Which Programs can be Solved?

This package lets you solve convex quadratic programs of the general form

in

A is anm × n matrix (the constraint matrix),b is anm -dimensional vector (the right-hand side),~ is anm -dimensional vector of relations from{ , , =,

, =,  }

}l is ann -dimensional vector of lower bounds forx , wherelj for all

{-

{-  }

}j u is ann -dimensional vector of upper bounds forx , whereuj for all

{

{  }

}j D is a symmetric positive-semidefiniten × n matrix (the quadratic objective function),c is ann -dimensional vector (the linear objective function), andc0 is a constant.

If

Solving the program means to find an ![]() x*

x* ![]() u

u

There might be no feasible solution at all, in which case the quadratic program is infeasible, or there might be feasible solutions of arbitrarily small objective function value, in which case the program is unbounded.

61.2 Design, Efficiency, and Robustness

The design of the package is quite simple. The linear or quadratic program to be solved is supplied in form of an object of a class that is a model of the concept QuadraticProgram (or some specialized other concepts, e.g. for linear programs). CGAL provides a number of easy-to-use and flexible models, see Section 61.3 below. The input data may be of any given number type, such as double, int, or any exact type.Then the program is solved using the function solve_quadratic_program (or some specialized other functions, e.g. for linear programs). For this, you also have to provide a suitable exact number type ET used in the solution process. In case of input type double, solution methods that use floating-point-filtering are chosen by default for certain programs (in some cases, this is not appropriate, and the default should be changed; see Section 61.8 for details).

The output of this is an object of Quadratic_program_solution<ET>

which you can in turn query for various things: what is the status of

the program (optimally solved, infeasible, or unbounded?), what are

the values of the optimal solution

You can in particular get certificates for the solution. In short, these are proofs that the output is correct. Thus, if you don't believe in the solution (whether it says ``optimally solved'', ``infeasible'', or ``unbounded''), you can verify it yourself by using the certificates. Section 61.7 says more about this.

61.2.1 Efficiency

The concept QuadraticProgram (as well as the other specialized ones) require a dense interface of the program, in terms of random-access iterators over the matrices and vectors of (QP). Zero entries therefore play no special role and are treated like all other entries by the interface.This has mainly historical reasons: the original motivation behind this package was low-dimensional geometric optimization where a dense representation is appropriate and efficient. In fact, the CGAL packages Min_annulus_d<Traits> and Polytope_distance_d<Traits> internally use the linear and quadratic programming solver.

As a user, however, you don't necessarily have to provide a dense representation of your program. You do not pass vectors or matrices to the solution functions, but rather specify the vectors and matrices through iterators. The iterator abstraction easily allows to build models that convert a sparse representation into a dense interface. The predefined models Quadratic_program<NT> and Quadratic_program_from_mps<NT> do exactly this; in using them, you can forget about the dense interface.

Nevertheless, if you care about efficiency, you cannot completely

ignore the issue. If

you think about a quadratic program in ![]() (n2 + mn)

(n2 + mn)![]() (mn)

(mn)

We can actually be quite precise about performance, in terms of the following parameters.

|

|

: |

the number of variables (or columns of |

|

|

: |

the number of constraints (or rows of |

|

|

: | the number of equality constraints, |

|

|

: |

the rank of the quadratic objective function matrix |

The time required to solve the problems is in most cases linear in

Here are the scenarios in which this applies:

- Quadratic programs with a small number of variables, but possibly a large number of inequality constraints,

- Linear programs with a small number of equality constraints but possibly a large number of variables,

- Quadratic programs with a small number of equality constraints and

D of small rank, but possibly with a large number of variables.

How small is small? If

If you have a problem where both

61.2.2 Robustness

Given that you use an exact number type in the function solve_quadratic_program (or in the other, specialized solution functions), the solver will give you exact rational output, for every convex quadratic program. It may fail to compute a solution only if- The quadratic program is too large (see the previous subsection on efficiency).

- The quadratic objective function matrix

D is not positive-semidefinite (see the discussion below). - The floating-point filter used by default for certain programs and input type double fails due to a double exponent overflow. This happens in rare cases only, and it does not pay off to sacrifice the efficiency of the filtered approach in order to cope with these rare cases. There are means, however, to avoid such problems by switching to a slower non-filtered variant, see Section 61.8.1.

- The solver internally cycles. This also happens in rare cases only. However, if you have a hunch that the solver cycles on your problem, there are means to switch to a slower variant that is guaranteed not to cycle, see Section 61.8.2.

The second item merits special attention. First, you may ask why the

solver does not check that ![]() (n2)

(n2)

Nevertheless, the solver contains some runtime checks

that may detect that the matrix

61.3 How to Enter and Solve a Program

In this section, we describe how you can supply and solve your problem, using the CGAL program models and solution functions. There are two essentially different ways to proceed, and we will discuss them in turn. In short,- you can let the model take care of your program data; you start from an empty program and then simply insert the non-zero entries, or read them from a file (more generally, any input stream) in MPSFormat. You can also change program entries at any time. This is usually the most convenient way if you don't want to care about representation issues;

- you can maintain the data yourself and only supply suitable random-access iterators over the matrices and vectors. This is advantageous if you already have the data (explicitly, or implicitly encoded, for example through iterators) and want to avoid copying of data. Typically, this happens if you write generic iterator-based code.

Our running example is the following quadratic program in two variables:

minimize

x2 + 4(y-4)2

(=

x2 + 4y2 - 32y + 64)

subject to

x + y

![]()

7

-x + 2y

![]()

4

x

![]()

0

y

![]()

0

y

![]()

4

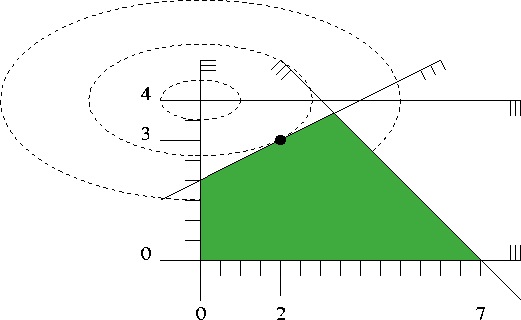

Figure 61.1 shows a picture. It depicts the five inequalities of the program, along with the feasible region (green), the set of points that satisfy all the five constraints. The dashed elliptic curves represent contour lines of the objective function, i.e., along each dashed curve, the objective function value is constant.

The global minimum of the objective function is attained at

the point

Figure 61.1: A quadratic program in two variables

61.3.1 Constructing a Program from Data

Here is how this quadratic program can be solved in CGAL according to the first way (letting the model take care of the data). We use int as the input type, and MP_Float or Gmpz (which is faster and preferable if GMP is installed) as the exact type for the internal computations. In larger examples, it pays off to use double as input type in order to profit from the automatic floating-point filtering that takes place then.For examples how to work with the input type double, we refer to Sections 61.5 and 61.8.

Note: For the quadratic objective function, the entries

of the matrix

File: examples/QP_solver/first_qp.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

#include <CGAL/basic.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// choose exact integral type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpz.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpz ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

// program and solution types

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program<int> Program;

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET> Solution;

int main() {

// by default, we have a nonnegative QP with Ax <= b

Program qp (CGAL::SMALLER, true, 0, false, 0);

// now set the non-default entries:

const int X = 0;

const int Y = 1;

qp.set_a(X, 0, 1); qp.set_a(Y, 0, 1); qp.set_b(0, 7); // x + y <= 7

qp.set_a(X, 1, -1); qp.set_a(Y, 1, 2); qp.set_b(1, 4); // -x + 2y <= 4

qp.set_u(Y, true, 4); // y <= 4

qp.set_d(X, X, 2); qp.set_d (Y, Y, 8); // !!specify 2D!! x^2 + 4 y^2

qp.set_c(Y, -32); // -32y

qp.set_c0(64); // +64

// solve the program, using ET as the exact type

Solution s = CGAL::solve_quadratic_program(qp, ET());

assert (s.solves_quadratic_program(qp));

// output solution

std::cout << s;

return 0;

}

Asuming that GMP is installed, the output of the of the above program is:

status: OPTIMAL objective value: 8/1 variable values: 0: 2/1 1: 3/1If GMP is not installed, the values are of course the same, but numerator and denominator might have a common divisor that is not factored out.

61.3.2 Constructing a Program from a Stream

Here, the program data must be available in MPSFormat (the MPSFormat page shows how our running example looks like in this format, and it briefly explains the format). Assuming that your working directory contains the file first_qp.mps, the following program will read and solve it, with the same output as before.

File: examples/QP_solver/first_qp_from_mps.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <CGAL/basic.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// choose exact integral type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpz.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpz ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

// program and solution types

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_from_mps<int> Program;

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET> Solution;

int main() {

std::ifstream in ("first_qp.mps");

Program qp(in); // read program from file

assert (qp.is_valid()); // we should have a valid mps file

// solve the program, using ET as the exact type

Solution s = CGAL::solve_quadratic_program(qp, ET());

// output solution

std::cout << s;

return 0;

}

61.3.3 Constructing a Program from Iterators

The following program again solves our running example from above, with the same output, but this time with iterators over data stored in suitable containers. You can see that we also store zero entries here (in

File: examples/QP_solver/first_qp_from_iterators.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <CGAL/basic.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// choose exact integral type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpz.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpz ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

// program and solution types

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_from_iterators

<int**, // for A

int*, // for b

CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator<CGAL::Comparison_result>, // for r

bool*, // for fl

int*, // for l

bool*, // for fu

int*, // for u

int**, // for D

int*> // for c

Program;

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET> Solution;

int main() {

int Ax[] = {1, -1}; // column for x

int Ay[] = {1, 2}; // column for y

int* A[] = {Ax, Ay}; // A comes columnwise

int b[] = {7, 4}; // right-hand side

CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator<CGAL::Comparison_result>

r( CGAL::SMALLER); // constraints are "<="

bool fl[] = {true, true}; // both x, y are lower-bounded

int l[] = {0, 0};

bool fu[] = {false, true}; // only y is upper-bounded

int u[] = {0, 4}; // x's u-entry is ignored

int D1[] = {2}; // 2D_{1,1}

int D2[] = {0, 8}; // 2D_{2,1}, 2D_{2,2}

int* D[] = {D1, D2}; // D-entries on/below diagonal

int c[] = {0, -32};

int c0 = 64; // constant term

// now construct the quadratic program; the first two parameters are

// the number of variables and the number of constraints (rows of A)

Program qp (2, 2, A, b, r, fl, l, fu, u, D, c, c0);

// solve the program, using ET as the exact type

Solution s = CGAL::solve_quadratic_program(qp, ET());

// output solution

std::cout << s;

return 0;

}

Note 1: The example shows an interesting feature of this approach: not all data need to come from containers. Here, the iterator over the vector of relations can be provided through the class Const_oneset_iterator<T>, since all entries of this vector are equal to CGAL::SMALLER. The same could have been done with the vector fl for the finiteness of the lower bounds.

Note 2: The program type looks a bit scary, with its total of 9 template arguments, one for each iterator type. In Section 61.5.1 we show how the explicit construction of this type can be circumvented.

61.4 Solving Linear and Nonnegative Programs

Let us reconsider the general form of (QP) from Section 61.1 above. If

From an interface perspective, this is just syntactic sugar: in the

model Quadratic_program<NT>, we can easily set the default bounds

so that a nonnegative program results, and a linear program is

obtained by simply not inserting any

The main reason for having dedicated solution methods for linear and

nonnegative programs is efficiency: if the solver knows that the program

is linear, it can save some computations compared to the general solver

that unknowingly has to fiddle around with a zero ![]() (n2)

(n2)

Similarly, if the solver knows that the program is nonnegative, it

will be more efficient than under the general bounds

![]() x

x ![]() u

u

Often, there are no bounds at all for the variables, i.e., all entries

of ![]()

![]()

61.4.1 The Linear Programming Solver

Let's go back to our first quadratic program from above and change it into a linear program by simply removing the quadratic part of the objective function:

minimize

- 32y + 64

subject to

x + y

![]()

7

-x + 2y

![]()

4

x

![]()

0

y

![]()

0

y

![]()

4

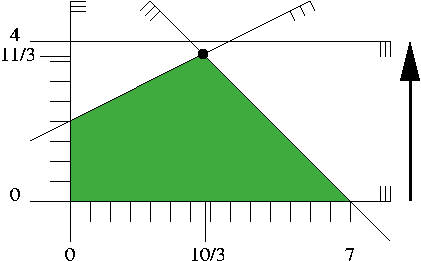

Figure 61.2 shows how this looks like. We will not

visualize a linear objective function with contour lines but with

arrows instead. The arrow represents the (direction) of the vector ![]() 7

7![]() 4

4

Figure 61.2: A linear program in two variables

Here is CGAL code for solving it, using the dedicated LP solver, and according to the three ways for constructing a program that we have already discussed in Section 61.3.

QP_solver/first_lp.cpp

QP_solver/first_lp_from_mps.cpp

QP_solver/first_lp_from_iterators.cpp

In all cases, the output is

status: OPTIMAL objective value: -160/3 variable values: 0: 10/3 1: 11/3

61.4.2 The Nonnegative Quadratic Programming Solver

If we go back to our first quadratic program and remove the constraint

minimize

x2 + 4(y-4)2

(=

x2 + 4y2 - 32y + 64)

subject to

x + y

![]()

7

-x + 2y

![]()

4

x,y

![]()

0

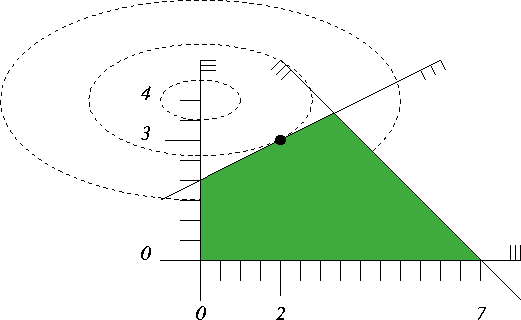

Figure 61.3 contains

the illustration; since the constraint ![]() 4

4

Figure 61.3: A nonnegative quadratic program in two variables

The following programs (using the dedicated solver for nonnegative quadratic programs) will therefore again output

status: OPTIMAL objective value: 8/1 variable values: 0: 2/1 1: 3/1

QP_solver/first_nonnegative_qp.cpp

QP_solver/first_nonnegative_qp_from_mps.cpp

QP_solver/first_nonnegative_qp_from_iterators.cpp

61.4.3 The Nonnegative Linear Programming Solver

Finally, a dedicated model and function is available for nonnnegative linear programs as well. Let's take our linear program from above and remove the constraint

minimize

- 32y

subject to

x + y

![]()

7

-x + 2y

![]()

4

x,y

![]()

0

This can be solved by any of the following three programs

QP_solver/first_nonnegative_lp.cpp

QP_solver/first_nonnegative_lp_from_mps.cpp

QP_solver/first_nonnegative_lp_from_iterators.cpp

The output will always be

status: OPTIMAL objective value: -352/3 variable values: 0: 10/3 1: 11/3

61.5 Working from Iterators

Here we present a somewhat more advanced example that emphasizes the usefulness of solving linear and quadratic programs from iterators. Let's look at a situation in which a linear program is given implicitly, and access to it is gained through properly constructed iterators.

The problem we are going to solve is the following: given points

![]() 1,...,

1,...,![]() n

n

![]() j=1n

j=1n ![]() j pj,

j pj, ![]() j=1n

j=1n ![]() j = 1,

j = 1,

![]() j

j ![]() 0

0

The problem of testing the existence of such ![]() j

j![]()

![]() d+1

d+1

![]() 1)

1) ![]() 1).

1).

Now, nonnegative ![]() 1,...,

1,...,![]() n

n

![]() j=1n

j=1n ![]() j(pj

j(pj ![]() 1) = (p

1) = (p ![]() 1),

1),

equivalently, if there are ![]() j · h/hj

j · h/hj

![]() j=1n µj qj = q, µj

j=1n µj qj = q, µj ![]() 0

0

The linear program now tests for the existence of nonnegative

File: examples/QP_solver/solve_convex_hull_containment_lp.h

#include <boost/config.hpp>

#include <boost/iterator/transform_iterator.hpp>

#include <CGAL/Kernel_traits.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// unary function to get homogeneous begin-iterator of point

template <class Point_d>

struct Homogeneous_begin {

typedef typename Point_d::Homogeneous_const_iterator result_type;

result_type operator() (const Point_d& p) const {

return p.homogeneous_begin();

}

};

// function to solve the LP that tests whether a point is in the

// convex hull of other points; the type ET is an exact type used

// for the internal computations

template <class Point_d, class RandomAccessIterator, class ET>

CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET>

solve_convex_hull_containment_lp (const Point_d& p,

RandomAccessIterator begin,

RandomAccessIterator end, const ET& dummy)

{

// Constraint matrix type: A[j][i] is the i-th homogeneous coordinate of p_j

typedef boost::transform_iterator

<Homogeneous_begin<Point_d>, RandomAccessIterator> A_it;

// Right-hand side type: b[i] is the i-th homogeneous coordinate of p

typedef typename Point_d::Homogeneous_const_iterator B_it;

// Relation type ("=")

typedef CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator<CGAL::Comparison_result> R_it;

// input number type

typedef typename CGAL::Kernel_traits<Point_d>::Kernel::RT RT;

// Linear objective function type (c=0: we only test feasibility)

typedef CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator<RT> C_it;

// the nonnegative linear program type

typedef

CGAL::Nonnegative_linear_program_from_iterators<A_it, B_it, R_it, C_it>

Program;

// ok, we are prepared now: construct program and solve it

Program lp (end-begin, // number of variables

p.dimension()+1, // number of constraints

A_it (begin), B_it (p.homogeneous_begin()),

R_it (CGAL::EQUAL), C_it (0));

return CGAL::solve_nonnegative_linear_program (lp, dummy);

}

To see this in action, let us call it with

File: examples/QP_solver/convex_hull_containment.cpp

#include <cassert>

#include <vector>

#include <CGAL/Cartesian_d.h>

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

#include "solve_convex_hull_containment_lp.h"

// choose exact floating-point type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpzf.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpzf ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

typedef CGAL::Cartesian_d<double> Kernel_d;

typedef Kernel_d::Point_d Point_d;

bool is_in_convex_hull (const Point_d& p,

std::vector<Point_d>::const_iterator begin,

std::vector<Point_d>::const_iterator end)

{

CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET> s =

solve_convex_hull_containment_lp (p, begin, end, ET(0));

return !s.is_infeasible();

}

int main()

{

std::vector<Point_d> points;

// convex hull: simplex spanned by {(0,0), (10,0), (0,10)}

points.push_back (Point_d ( 0.0, 0.0));

points.push_back (Point_d (10.0, 0.0));

points.push_back (Point_d ( 0.0, 10.0));

for (int i=0; i<=10; ++i)

for (int j=0; j<=10; ++j) {

// (i,j) is in the simplex iff i+j <= 10

bool contained = is_in_convex_hull

(Point_d (i, j), points.begin(), points.end());

assert (contained == (i+j<=10));

}

return 0;

}

61.5.1 Using Makers

You already noticed in the previous example that the actual template arguments for CGAL::Nonnegative_linear_program_from_iterators<A_it, B_it, R_it, C_it> can be quite elaborate, and this only gets worse if you plug more iterators into each other. In general, you want to construct a program from given expressions for the iterators, but the types of these expressions are probably very complicated and difficult to look up.You can avoid the explicit construction of the type CGAL::Nonnegative_linear_program_from_iterators<A_it, B_it, R_it, C_it> if you only need an expression of it, e.g. to pass it directly as an argument to the solving function. Here is an alternative version of QP_solver/solve_convex_hull_containment_lp.h that shows how this works. In effect, you get shorter and more readable code.

File: examples/QP_solver/solve_convex_hull_containment_lp2.h

#include <boost/config.hpp>

#include <boost/iterator/transform_iterator.hpp>

#include <CGAL/Kernel_traits.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// unary function to get homogeneous begin-iterator of point

template <class Point_d>

struct Homogeneous_begin {

typedef typename Point_d::Homogeneous_const_iterator result_type;

result_type operator() (const Point_d& p) const {

return p.homogeneous_begin();

}

};

// function to test whether point is in the convex hull of other points;

// the type ET is an exact type used for the computations

template <class Point_d, class RandomAccessIterator, class ET>

CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET>

solve_convex_hull_containment_lp (const Point_d& p,

RandomAccessIterator begin,

RandomAccessIterator end, const ET& dummy)

{

// construct program and solve it

return CGAL::solve_nonnegative_linear_program

(CGAL::make_nonnegative_linear_program_from_iterators

(end-begin, // n

p.dimension()+1, // m

boost::transform_iterator

<Homogeneous_begin<Point_d>, RandomAccessIterator>(begin), // A

typename Point_d::Homogeneous_const_iterator (p.homogeneous_begin()),// b

CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator<CGAL::Comparison_result>(CGAL::EQUAL), // ~

CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator

<typename CGAL::Kernel_traits<Point_d>::Kernel::RT> (0)), dummy); // c

}

61.6 Important Variables and Constraints

If you have a solutionThe following example shows how we can access the important variables, using the iterators basic_variable_indices_begin() and basic_variable_indices_end().

We generate a set of points that form a 4-gon in

File: examples/QP_solver/important_variables.cpp

#include <cassert>

#include <vector>

#include <CGAL/Cartesian_d.h>

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

#include "solve_convex_hull_containment_lp2.h"

typedef CGAL::Cartesian_d<double> Kernel_d;

typedef Kernel_d::Point_d Point_d;

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<CGAL::MP_Float> Solution;

int main()

{

std::vector<Point_d> points;

// convex hull: 4-gon spanned by {(1,0), (4,1), (4,4), (2,3)}

points.push_back (Point_d (1, 0)); // point 0

points.push_back (Point_d (4, 1)); // point 1

points.push_back (Point_d (4, 4)); // point 2

points.push_back (Point_d (2, 3)); // point 3

// test all 25 integer points in [0,4]^2

for (int i=0; i<=4; ++i)

for (int j=0; j<=4; ++j) {

Point_d p (i, j);

Solution s = solve_convex_hull_containment_lp

(p, points.begin(), points.end(), CGAL::MP_Float());

std::cout << p;

if (s.is_infeasible())

std::cout << " is not in the convex hull\n";

else {

assert (s.is_optimal());

std::cout << " is a convex combination of the points ";

Solution::Index_iterator it = s.basic_variable_indices_begin();

Solution::Index_iterator end = s.basic_variable_indices_end();

for (; it != end; ++it) std::cout << *it << " ";

std::cout << std::endl;

}

}

return 0;

}

It turns out that exactly three of the four points contribute to any convex combination, even through there are lattice points that lie in the convex hull of less than three of the points. This shows that the set of basic variables that we access in the example does not necessarily coincide with the set of important variables as defined above. In fact, it is only guaranteed that a non-basic variable attains one of its bounds, but there might be basic variables that also have this property. In linear and quadratic programming terms, such a situation is called a degeneracy.

There is also the concept of an important constraint: this is

typically a constraint in the system

Again, we have a disagreement

between ``basic'' and ``important'': it is guaranteed that all

basic constraints are satisfied with equality at

61.7 Solution Certificates

Suppose the solver tells you that the problem you have entered is infeasible. Why should you believe this? Similarly, you can quite easily verify that a claimed optimal solution is feasible, but why is there no better one?Certificates are proofs that the solver can give you in order to convince you that what it claims is indeed true. The archetype of such a proof is Farkas Lemma [MG06].

Farkas Lemma: Either the inequality system

A x

![]()

b

x

![]()

0

has a solution

y

![]()

0

yTA

![]()

0

yTb

<

0,

but not both.

Thus, if someone wants to convince you that the first system in

the Farkas Lemma is infeasible, that person can simply give you

a vector

Here we show how the solver can convince you. We first set up an infeasible

linear program with constraints of the type ![]() b, x

b, x ![]() 0

0

File: examples/QP_solver/infeasibility_certificate.cpp

#include <cassert>

#include <CGAL/basic.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// choose exact integral type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpz.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpz ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

// program and solution types

typedef CGAL::Nonnegative_linear_program_from_iterators

<int**, // for A

int*, // for b

CGAL::Comparison_result*, // for r

int*> // for c

Program;

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET> Solution;

// we demonstrate Farkas Lemma: either the system

// A x <= b

// x >= 0

// has a solution, or there exists y such that

// y >= 0

// y^TA >= 0

// y^Tb < 0

// In the following instance, the first system has no solution,

// since adding up the two inequalities gives x_2 <= -1:

// x_1 - 2x_2 <= 1

// -x_1 + 3x_2 <= -2

// x_1, x_2 >= 0

int main() {

int Ax1[] = { 1, -1}; // column for x1

int Ax2[] = {-2, 3}; // column for x2

int* A[] = {Ax1, Ax2}; // A comes columnwise

int b[] = {1, -2}; // right-hand side

CGAL::Comparison_result

r[] = {CGAL::SMALLER, CGAL::SMALLER}; // constraints are "<="

int c[] = {0, 0}; // zero objective function

// now construct the linear program; the first two parameters are

// the number of variables and the number of constraints (rows of A)

Program lp (2, 2, A, b, r, c);

// solve the program, using ET as the exact type

Solution s = CGAL::solve_nonnegative_linear_program(lp, ET());

// get certificate for infeasibility

assert (s.is_infeasible());

Solution::Infeasibility_certificate_iterator y =

s.infeasibility_certificate_begin();

// check y >= 0

assert (y[0] >= 0);

assert (y[1] >= 0);

// check y^T A >= 0

assert (y[0] * A[0][0] + y[1] * A[0][1] >= 0);

assert (y[0] * A[1][0] + y[1] * A[1][1] >= 0);

// check y^T b < 0

assert (y[0] * b[0] + y[1] * b[1] < 0);

return 0;

}

There are similar certificates for optimality and unboundedness

that you can see in action in the programs

QP_solver/optimality_certificate.cpp and

QP_solver/unboundedness_certificate.cpp.

The underlying variants of Farkas Lemma are somewhat more

complicated, due to the mixed relations in

61.8 Customizing the Solver

Sometimes it is necessary to alter the default behavior of the solver. This can be done by passing a suitably prepared object of the class Quadratic_program_options to the solution functions. Most options concern ``soft'' issues like verbosity, but there are two notable case where it is of critical importance to be able to change the defaults.61.8.1 Exponent Overflow in Double Using Floating-Point Filters

The filtered version of the solver that is used for some problems by default on input type double internally constructs double-approximations of exact multiprecision values. If these exact values are extremely large, this may lead to infinite double values and incorrect results. In debug mode, the solver will notice this through a certificate cross-check in the end (or even earlier). In this case, it is advisable to explicitly switch to a non-filtered pricing strategy, see Quadratic_program_pricing_strategy.

Hint:

If you have a program where the number of variables

61.8.2 The Solver Internally Cycles

Consider the following program. It reads a nonnegative linear program from the file cycling.mps (which is in the example directory as well), and then solves it in verbose mode, using Bland's rule, see Quadratic_program_pricing_strategy.

File: examples/QP_solver/cycling.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <CGAL/basic.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// choose exact floating-point type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpzf.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpzf ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

// program and solution types

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_from_mps<double> Program;

typedef CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET> Solution;

int main() {

std::ifstream in ("cycling.mps");

Program lp(in); // read program from file

assert (lp.is_valid()); // we should have a valid mps file...

assert (lp.is_linear()); // ... and it should be linear...

assert (lp.is_nonnegative()); // as well as nonnegative

// solve the program, using ET as the exact type

// choose verbose mode and Bland pricing

CGAL::Quadratic_program_options options;

options.set_verbosity(1); // verbose mode

options.set_pricing_strategy(CGAL::QP_BLAND); // Bland's rule

options.set_auto_validation(true); // automatic self-check

Solution s = CGAL::solve_nonnegative_linear_program(lp, ET(), options);

assert (s.is_valid()); // did the self-check succeed?

// output solution

std::cout << s;

return 0;

}

If you comment the line

options.set_pricing_strategy(CGAL::QP_BLAND); // Bland's ruleyou will see that the solver cycles: the verbose mode outputs the same sequence of six iterations over and over again. By switching to QP_BLAND, the solution process typically slows down a bit (it may also speed up in some cases), but now it is guaranteed that no cycling occurs.

In general, the verbose mode can be of use when you are not sure whether the solver ``has died'', or whether it simply takes very long to solve your problem. We refer to the class Quadratic_program_options for further details.

61.9 Some Benchmarks

Here we want to show what you can expect from the solver's performance in a specific application; we don't know whether this application is typical in your case, and we make no claims whatsoever about the performance in other applications.Still, the example shows that the performance can be dramatically affected by switching between pricing strategies, and we give some hints on how to achieve good performance in general.

The application is the one already discussed in Section 61.5 above: testing whether a point is in the convex hull of other points. To be able to switch between pricing strategies, we add another parameter of type Quadratic_program_options to the function solve_convex_hull_containment_lp that we pass on to the solution function:

File: examples/QP_solver/solve_convex_hull_containment_lp3.h

#include <boost/config.hpp>

#include <boost/iterator/transform_iterator.hpp>

#include <CGAL/Kernel_traits.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_options.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_models.h>

#include <CGAL/QP_functions.h>

// unary function to get homogeneous begin-iterator of point

template <class Point_d>

struct Homogeneous_begin {

typedef typename Point_d::Homogeneous_const_iterator result_type;

result_type operator() (const Point_d& p) const {

return p.homogeneous_begin();

}

};

// function to test whether point is in the convex hull of other points;

// the type ET is an exact type used for the computations

template <class Point_d, class RandomAccessIterator, class ET>

CGAL::Quadratic_program_solution<ET>

solve_convex_hull_containment_lp (const Point_d& p,

RandomAccessIterator begin,

RandomAccessIterator end, const ET& dummy,

const CGAL::Quadratic_program_options& o)

{

// construct program and solve it

return CGAL::solve_nonnegative_linear_program

(CGAL::make_nonnegative_linear_program_from_iterators

(end-begin, // n

p.dimension()+1, // m

boost::transform_iterator

<Homogeneous_begin<Point_d>, RandomAccessIterator>(begin), // A

typename Point_d::Homogeneous_const_iterator (p.homogeneous_begin()),// b

CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator<CGAL::Comparison_result>(CGAL::EQUAL), // ~

CGAL::Const_oneset_iterator

<typename CGAL::Kernel_traits<Point_d>::Kernel::RT> (0)), // c

dummy, o);

}

Now let us test containment of the origin in the convex hull

of

File: examples/QP_solver/convex_hull_containment_benchmarks.cpp

#include <vector>

#include <CGAL/Cartesian_d.h>

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

#include <CGAL/Random.h>

#include <CGAL/Timer.h>

#include "solve_convex_hull_containment_lp3.h"

// choose exact floating-point type

#ifdef CGAL_USE_GMP

#include <CGAL/Gmpzf.h>

typedef CGAL::Gmpzf ET;

#else

#include <CGAL/MP_Float.h>

typedef CGAL::MP_Float ET;

#endif

typedef CGAL::Cartesian_d<double> Kernel_d;

typedef Kernel_d::Point_d Point_d;

int main()

{

const int d = 10; // change this in order to experiment

const int n = 100000; // change this in order to experiment

// generate n random d-dimensional points in [0,1]^d

CGAL::Random rd;

std::vector<Point_d> points;

for (int j =0; j<n; ++j) {

std::vector<double> coords;

for (int i=0; i<d; ++i)

coords.push_back(rd.get_double());

points.push_back (Point_d (d, coords.begin(), coords.end()));

}

// benchmark all pricing strategies in turn

CGAL::Quadratic_program_pricing_strategy strategy[] = {

CGAL::QP_CHOOSE_DEFAULT, // QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG

CGAL::QP_DANTZIG, // Dantzig's pivot rule...

CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_DANTZIG, // ... with partial pricing

CGAL::QP_BLAND, // Bland's pivot rule

CGAL::QP_FILTERED_DANTZIG, // Dantzig's filtered pivot rule...

CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG // ... with partial pricing

};

CGAL::Timer t;

for (int i=0; i<6; ++i) {

// test strategy i

CGAL::Quadratic_program_options options;

options.set_pricing_strategy (strategy[i]);

t.reset(); t.start();

// is origin in convex hull of the points? (most likely, not)

solve_convex_hull_containment_lp

(Point_d (d, CGAL::ORIGIN), points.begin(), points.end(),

ET(0), options);

t.stop();

std::cout << "Time (s) = " << t.time() << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

If you compile with the macros NDEBUG or CGAL_QP_NO_ASSERTIONS set (this is essential for good performance!!), you will see runtimes that qualitatively look as follows (on your machine, the actual runtimes will roughly be some fixed multiples of the numbers in the table below, and they might vary with the random choices). The default choice of the pricing strategy in that case is QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG.

| strategy | runtime in seconds | |

| CGAL::QP_CHOOSE_DEFAULT | | | 0.32 |

| CGAL::QP_DANTZIG | | | 10.7 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_DANTZIG | | | 3.72 |

| CGAL::QP_BLAND | | | 3.65 |

| CGAL::QP_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 0.43 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 0.32 |

We clearly see the effect of filtering: we gain a factor of ten, roughly, compared to the next best non-filtered variant.

61.9.1 d=3 , n=1,000,000

The filtering effect is amplified if the points/dimension ratio becomes

larger. This is what you might see in dimension three, with one million

points.

| strategy | runtime in seconds | |

| CGAL::QP_CHOOSE_DEFAULT | | | 1.34 |

| CGAL::QP_DANTZIG | | | 47.6 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_DANTZIG | | | 15.6 |

| CGAL::QP_BLAND | | | 16.02 |

| CGAL::QP_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 1.89 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 1.34 |

In general, if your problem has a high variable/constraint or constraint/variable ratio, then filtering will typically pay off. In such cases, it might be beneficial to encode your problem using input type double in order to profit from the filtering (but see the issue discussed in Section 61.8.1).

61.9.2 d=100 , n=100,000

Conversely, the filtering effect deteriorates if the points/dimension ratio

becomes smaller.

| strategy | runtime in seconds | |

| CGAL::QP_CHOOSE_DEFAULT | | | 3.05 |

| CGAL::QP_DANTZIG | | | 78.4 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_DANTZIG | | | 45.9 |

| CGAL::QP_BLAND | | | 33.2 |

| CGAL::QP_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 3.36 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 3.06 |

61.9.3 d=500 , n=1,000

If the points/dimension ratio tends to a constant, filtering is no

longer a clear winner. The reason is that in this case,

the necessary exact calculations with multiprecision numbers

dominate the overall runtime.

| strategy | runtime in seconds | |

| CGAL::QP_CHOOSE_DEFAULT | | | 2.65 |

| CGAL::QP_DANTZIG | | | 5.55 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_DANTZIG | | | 5.6 |

| CGAL::QP_BLAND | | | 4.46 |

| CGAL::QP_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 2.65 |

| CGAL::QP_PARTIAL_FILTERED_DANTZIG | | | 2.61 |

In general, if you have a program where the number of variables and the number of constraints have the same order of magnitude, then the saving gained from using the filtered approach is typically small. In such a situation, you should consider switching to a non-filtered variant in order to avoid the rare issue discussed in Section 61.8.1 altogether.

Navigation: Up, Table of Contents, Package Overview, Bibliography, Index, Title Page , Acknowledging CGAL